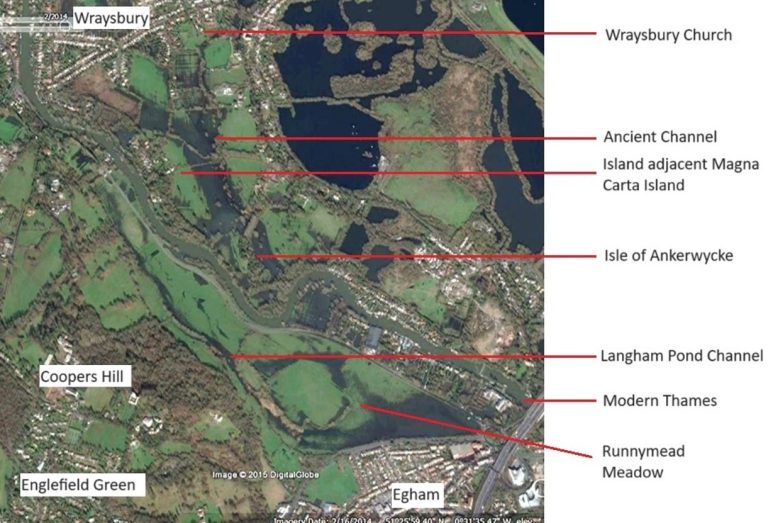

Aerial Image showing landscape after flooding. A broad 'Paleochannel' can be seen to the left of the image. It would be 5 times wider than the present Thames, and flows around the ancient island of Ankerwycke.

Close up of the Paleo-channel showing the water flowing around the ancient island of Ankerwycke.

Poland's River Narew in Stekowa Gora. This represents how the braided Thames once looked.

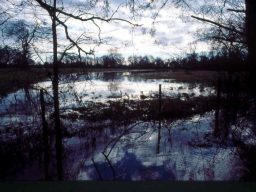

Flooding at Ankerwycke shows the former channel that runs to the east of the island site.

The Ancient Landscape:

The Last Ice Age

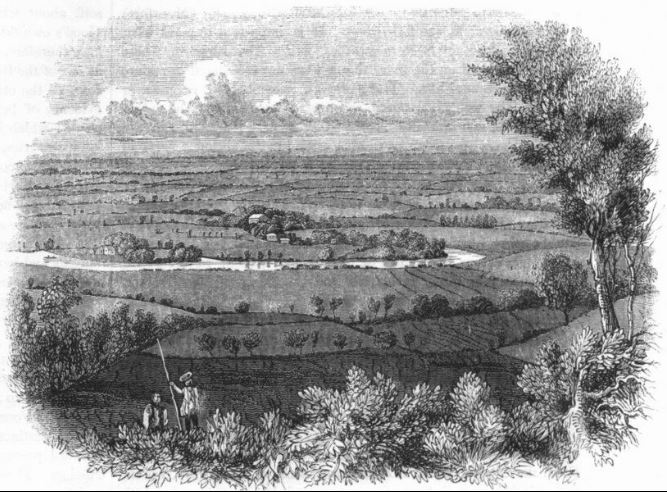

10,000 years ago, just after the last Ice Age, the landscape here was very different: Vast quantities of melt water had carved out great swathes of land and gravel had been deposited in the newly formed river valleys. Gravel terraces and islands developed, along with a network of river channels which created a braided appearance to the landscape.

As the river developed over the centuries, new meanders were created and redundant channels became filled with silt, eventually becoming oxbow lakes and isolated linear channels. Many of these ‘paleochannels’ lie hidden under layers of silt from more recent episodes of flooding. However in excavations at Kings Mead Quarry, Horton, several former channels have been discovered. More recent, the area known as Langhams Pond at Runnymede, is likely to have been one of these former channels, and was later known to be maintained as a series of fisheries in Medieval times.

At times of flood, it is still possible to see one of these Paleochannels, that runs through the estate, and 2 ancient islands are discernible – that of the Isle of Ankerwycke to the south, and the larger island to the north, near Magna Carta Lane.

The Ancient Landscape : Neolithic & Bronze Age

Ritual / Spiritual sites

The river during the Neolithic Period was important for trade, transport and communications, and became synonymous with the construction of monuments, being used for spiritual or ritual purposes. Locally there were several important sites: At Yeoveney Lodge, near Staines (now under M25) – a Neolithic causeway camp was discovered on a gravel spur at the confluence of the River Colne and River Thames. Comprising two concentric circuits of interrupted ditch, it enclosed an area of about 2.4 hectares. There was also the Stanwell Circus and Heathrow Circus, which were processionary routes leading away from the river. Near Staines is also recorded the site of ‘Nagen Stones’. This site was mentioned in the Saxon Preambulation Charter, alluding to 9 standing stones.

During the Bronze Age the river grew in importance- resources such as willow, reed and fish could be harvested, the fertile flood plains and gravel terraces used for grazing of animals and growing of crops. Archaeological excavations have confirmed extensive occupation of these terraces, dating to the Neolithic and Bronze Age: For example to the north in Wraysbury Village, Bucket Urns were found in excavations in 1979. At South Lea Farm, Datchet extensive fieldwalking and geophysics has demonstrated farming and settlement for over 3000 years.

Likewise at gravel quarries at Kingsmead, Horton and Poyle evidence was discovered pertaining paleochannels, round houses, butchering of animals and farming activities.

So it is not beyond the realms of possibility to suggest that the Isle of Ankerwycke, and its’ adjacent terraces were also occupied during the Bronze Age, or played an important role in the landscape.

Excavations at Runnymede Bridge in 1981 demonstrated an important Bronze Age trading site. Riverside settlements are also recorded throughout the Thames Valley

Dredging of the River Thames during the 19th century produced many finds. In the channel at Runnymede relics such as flint hand axes, a medieval sword and this Iron Age Terret ring were discovered.

Flint was extensively used to make tools during the Neolithic and Bronze Age. It was very versatile and could be worked to produce blades, knives, scrapers, arrow heads, adzes and axes.

Scrapers were a very common tool. They were used to remove the fur and fat off animal hides. Only the leading edge of the tool was worked to produce a sharp surface to scrape against the stretched hides.

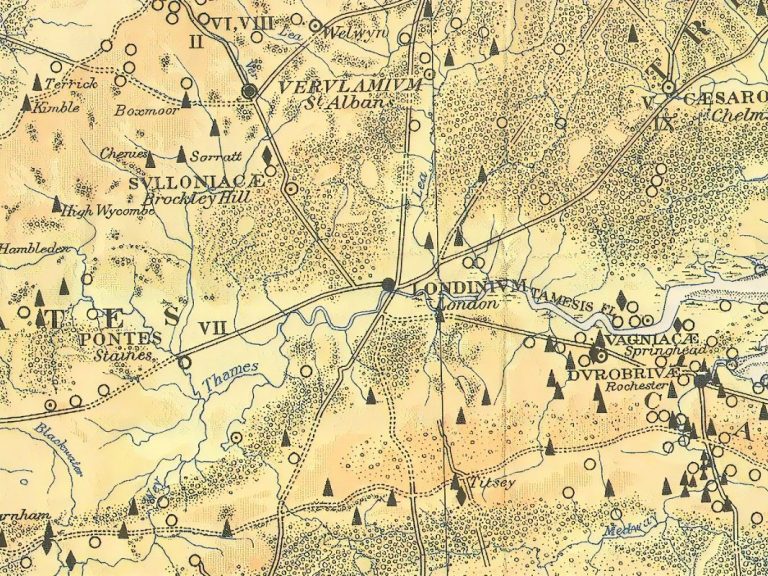

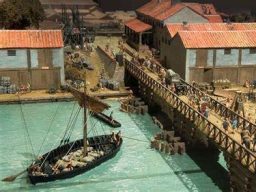

Map showing Roman Roads. The road from London to Silchester (Calleva) passed through Staines (Ad Pontes).

The original Roman bridge at Staines was considered the first location the Thames could be crossed west of London.

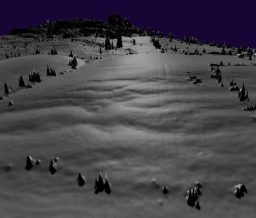

Coopers Hill. Looking east. The regular terraces, each of 5 ft high and 10 ft wide could be interpretated as remnant of historic clay extraction.

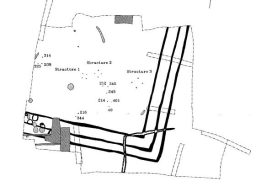

Detail from the Wayland excavations in Wraysbury showing the triple ditches. Were these once enclosing a fort?

The Lidar for Coopers Hill suggests this evidence is more akin to hill slump,

Photo of the Wayland excavations at Wraysbury showing the ditches insiti.

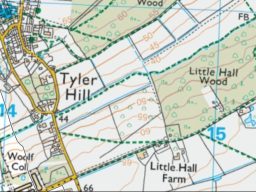

Comparisons have been made to Tyler Hill, Canterbury, where Roman kilns were also discovered. But without further exploration at Runnymede, it is hard to prove.

Roman Ankerwycke

By Roman Times, military roads were constructed to primarily facilitate movement of troops. However as the centuries passed, goods and livestock also used these routes. The main route from London westward to Silchester crossed the Thames about 2km to the south of Ankerwycke, at Staines upon Thames, which is understood to be the first crossing of the Thames west of London. It was once known as ‘Ad Pontes’, meaning ‘At the Bridges’. The site chosen utilised the mid stream gravel islands to locate the piers of at least 2 bridges. A ford here would be impractical due to the depth and width of the river. A Town also quickly developed on the north bank of the Thames, controlling the river crossing.

The Thames was not the only River in the area that the Romans had to negotiate. Just west of Ad Pontes was tributary of the Thames - The River Colne. It was a broad river, originating at Colney heath near Hatfield, and extending for over 36 miles.

A conjectured second crossing may well have been located west of the Colne delta, adjacent to Ankerwycke: Mentioned in a Saxon Preambulation Charter, a crossing called Lodderlake Bridge was located approximately between the modern day Magna Carta Island and the Bells of Ousley. The route was first identified as Route 163B which has been traced with some certainty from Langley Park to Chorleywood. Evidence from surviving parish boundaries and other landscape features demonstrate various linear features that conveniently align, perhaps alluding to a possible Roman Road, of about 24 miles in length from Lodderlake to St Albans.

Around settlements such as Ad Pontes. vast farms and industry sprung up: Grain was produced to supply bread and ale for communities and the legions, Cattle farms established for their milk and meat. It is evident that industries such as clay extraction was undertaken on an enormous scale on Coopers Hill : Kiln fired bricks and tiles made here were then transported by barge from an area called Tilebedburn and transferred to boats at Lodderlake on the Thames to other Roman sites. Indeed the earthworks of this extraction can be seen extending as regular cut terraces along Coopers Hill.

Additionally Roman evidence near Ankerwycke alludes to a Roman settlement close by, in the vicinity of the village of Wraysbury. Pottery, metal work and burials were discovered in 1979 by Wessex Archaeology. Furthermore, excavations at Waylands School in 1997 found the corner of a triple ditch as well as quantities of Roman pottery. Could this be a Roman station controlling the Lodderlake Bridge river crossing?

The Ancient Landscape : Saxon

After the Romans left, the region was continued to be settled by farmers and traders. Saxon settlements developed at Wraysbury and Old Windsor, the latter becoming an important Saxon Hall and Manor. Wraysbury, known then as Wyrardisbury, is thought to have developed as a Saxon fortified site, perhaps called ‘Wïgrǣd’s fort’.

As Pagan society embraced Christianity, the Thames valley became popular for the foundation of Abbeys: Reading, Chertsey, Syon and Barking were established in the 7th Century along the margins of the Thames. They grew in prosperity and owned vast areas of land. However some of these sites were sacked in the Danish raids during the 9th -11th centuries. In 1009 Danes were recorded to assemble at Staines Bridge, and perhaps sailed up the Thames.

The name ‘Ankerwycke’ is also religious, deriving from the word ‘Anchorite’, which is a hermit, or a solitary religious person worshipping god. The second syllable ‘wycke’ means either a ‘bend in the river’ or ‘a wooded island’. It suggests that prior to the Norman Conquest part of the site was occupied by a self sufficient pious man or woman, who occupied a timber building, or simple church like structure. People would bring gifts of food to the hermit, and in return they would pray for their souls.

This wooded isle most probably contained the Ankerwycke Yew. Perhaps planted, perhaps a survivor from the ancient wildwood that once covered vast areas of land, its association here almost certainly linked with pagan beliefs. It was commonplace to substitute Pagan festivals with Christian feast days, and the same can be said regarding the Pagan sites, being superseded with Christian churches and other religious sites. So it would make sense for the former anchorite cell to later be replaced by a monastic order. Which ever the case, the yew became entwined in the site’s history, and a symbolic tree to society at that time. (See Ankerwycke Yew page)

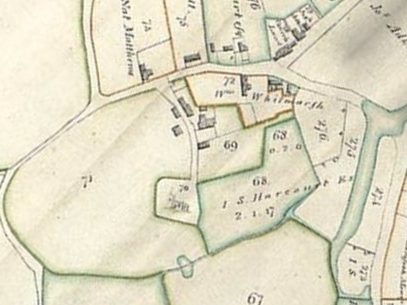

Extract from 1800 Map: The area of the Saxon ‘burgh’ can be seen as an oval enclosure around the present church. Earthworks still exist on the southside of the church that reflect terracing and possible boundary defences from that time.

The footprint of the Saxon Boundary is still evident today, despite modern changes to the land-scape

Earthworks are visible on the southside of the churchyard. These may turn out to be natural river gravel terraces.

Wyrardisbury would have been farmed as a mixed estate, also benefiting from the fisheries in the Thames.

Next page: Medieval History

© Copyright. All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.