New Owners

After the Dissolution, the estates of Ankerwycke and Ankerwycke Purnish were leased out by the Crown.

Lease by John Norreys Nov 10th 1536

A 21 year lease was granted by Henry VIII of:

"the house and site of the late priory of Ankerwyke, Bucks, and certain lands, meadows, and pastures called severally Ankerwyke, Halfelde, Longmede, Gore mede, Daymede, More mede, and Redyngfelde, with the herbage of a grove of wood called Rowyke, and tithes of all the premises; term 21 years; rent, 6 l. 9 s. 4d".

The identity of Norris is most likely Berkshire-born John Norreys (1480-1564) . He was the eldest son of Sir Edward Norreys and Lady Frideswide Lovell of Yattendon Castle, NE of Newbury. He was an Esquire of the Body to King Henry VIII and, afterwards, Usher of the Outer Chamber both to Kings Henry VIII and Edward VI. It is recorded that William Byrd, Husbandman of Wraysbury “dwelt there when Mr Norris was there” (TNA C24/40), which would suggest the farmland was sublet, presumably with Byrd and/Norris both occupying different buildings associated with the Priory, suggesting elements survived the dissolution. (Contrary to D&S Lysons (Magna Britannica 1813) who stated the whole site was ruinous).

Early in 1538 Bisham Abbey was refounded by Henry VIII who bequeathed Ankerwycke to them, to enable the Monks to receive income from the rents there. William Byrd continued to farm Ankerwycke when Bisham took over as owners, perhaps purely for security of rental income for the new Abbey. Indeed at Greenford Manor it is recorded that the tenant farmer continued to be James Cole, who had farmed it for Ankerwycke Priory, and so it’s most probable that similarities occurred at many of Ankerwycke’s former holdings. Unfortunately Bisham’s revival was very short-lived, and in June 1538, it was once again dissolved, the lands temporarily passing for the second time to Henry VIII.

Lease to Andrew Windsor 4th August 1539

A year later, the Ankerwycke possessions were granted to Andrew Lord Windsor (1467-1543) of Stanwell [TNA E147/4/25]. The Manor of Stanwell had been the family’s ancestral home since 1086, and from where one William Fitz Othere, undertook his role as Constable of Windsor Castle. Subsequent descendants changed their name to Windsor to honour this noble position.

Andrew Windsor was also well connected with the King and Church. He was Master of the Great Wardrobe for Henry VIII between the years 1504–1543, and was present at the Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520. Windsor had direct links with Ankerwycke nunnery, as he was employed by the Prioress as their Steward, receiving £1 annually for his commitments there. He also formerly held a lease from Ankerwycke of Stanwell Park in 1516, which presumably abutted his land there.

In 1542 the demesne lands of Ankerwycke were sublet by his son, Thomas Windsor, to husbandman John Thornton and his wife, Joan Thornton (nee Norwood) of Staines. They held a lease of 87 acres at a rent of £6 9s 4d a year which included ‘certain barns and stables’, suggesting that the farm buildings remained intact, and that other buildings were not to be used by them, (possibly alluding to them being leased separately, or retained by Windsor for other purposes).

But in 1543, Henry VIII fell out of favour with the Windsor's, so the King forced an exchange with them, swapping Crown lands in Worcestershire with property of the Windsor’s, including the Manor of Stanwell and the Manor of Ankerwycke.

The priory lands returned once again to the Crown, and came to Edward VI upon the death of Henry VIII in 1547.

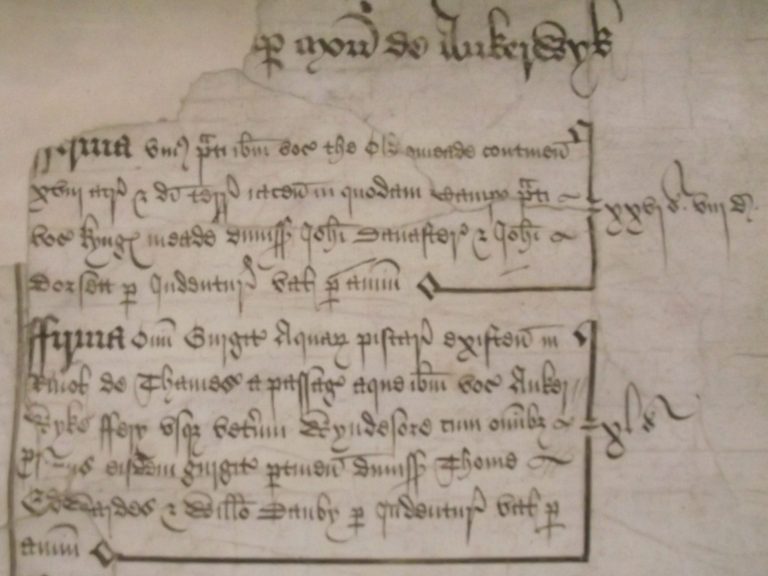

[TNA E147/4/25] Details of Windsor's lease at Ankerwycke included the following:

" the grant of the church, steeple and churchyard of the late priory of Ankerwyck;

all the weirs and fisheries in the River Thames from a passage called Ankerwycke Ferry to Old Windesore... which weirs Thomas Edwards and William Danby now hold; value 40sh

the pastures called Tynsett late in the tenure of Dav Eyre and a meadow now in the tenure of William Carter; 2 acres of land in Hamlett gate; a meadow called Wye acre; and all other lands there in the tenure of William Downes in Wyrerdisbury, a wood called Grethege late in the tenure of William Hill in “said” co Midd. (? Bucks); all which premises belonged to the late priory of Ankerwycke."

The terms of his lease also enabled his two sons to continue the lease, under a term called 'Tail Male' ie one son after the other.

Purchase by Sir Thomas Smith 1550

The young Boy-King, Edward VI offered Sir Thomas Smith Ankerwycke in exchange for other lands he held. Smith had previously been Edward's teacher, nearly a decade earlier. Whilst it might be considered a gift from Edward to reward or commend Smith for his efforts, it was far from such a generous offer: Not only did Smith have to return other property he had formerly leased from the Crown in Derby, Pontefract, York and Westminster (valued at £32 14sh 10d), but he further had to pay Edward £414 10sh 4d for the leases of Ankerwycke, Ankerwycke Purnish and the Northamptonshire Manors of Overton and Overston as well as and Bynderton in Sussex.

Who was Sir Thomas Smith?

Sir Thomas Smith (1513-1578) was an extremely intelligent and competent man. He studied Latin, Greek and Mathematics at Queens College Cambridge. His abilities were quickly recognised, and he was appointed Fellow there, lecturing on subjects such as natural philosophy and Greek. A keen Protestant, Smith tutored numerous students including Edward de Vere, John Ponet, Richard Eden and William Cecil. He remained close friends with these men, and on more than one occasion, the lives of these individuals greatly contributed to Smith’s future success and career.

In 1542 Smith was made Vice Chancellor at Cambridge, and his Protestant views, brought him into Royal prominence at the accession of 9-year-old Edward VI, and so Smith became Tutor to the young King.

On 15 April 1548, he married a French woman, Elizabeth Carkett, daughter of French Printer William Carkett who brought to Smith a dowry of 1000 Marks (£666). They held property in London, at Cannon Row, Westminster, and Smith probably took a lease of a property in the vicinity of Eton.

Later in 1548 Smith was made Secretary of State and was knighted the same year for his services to the Crown. During King Edward’s short reign of six years, Smith changed the culture of the nation. With Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cramer, he helped to publish the Book of Common Prayer in English and was associated with the building of hundreds of grammar schools, to educate ordinary boys. (Suzanne Elliot NT)

However, in September 1549, his loyalty to Lord Protector Somerset nearly cost him his life:

As a result of failing policies and uprisings in England, a coup, led by Lord Chamberlin Dudley, Earl of Warwick, forced the removal from office of Somerset. Somerset and Smith were imprisoned in the Tower of London from October 1549 until February 1550. However shortly later Somerset was accused of treason, and was executed, however Smith was much more fortunate, paying fines and loosing all of his public offices.

Retiring temporarily from politics, Smith resumed life as Provost at Eton. However shortly later Edward VI offered Smith property nearby - namely Ankerwycke. Its convenience to Eton and London made it a perfect base, and Smith probably relished the opportunity to move there, owning both the Priory and the land.

However there was the small matter of the sitting tenant - Joan Thornton. Her existing lease at Ankerwycke was described as:

“the Mansyon house alias farm and all the demesne Landes medowes feadinges and pastures to the same belonging and appert(ayn)ing With all and singular app(ur)ten(en)ces called the Ancowyke sett lyinge And being in the p(ar)isshe of Wiresbury in the counties of Midd(lesex)".[Eton Archives Ref: Coll STA S 3].

Portrait of Sir Thomas Smith, held at Eton College Library Archives

Eton College. Smith was Provost here from 1549

Smith utilised his position at Eton to sway Joan Thornton to exchange her lease of the Farm and land at Ankerwycke for one at Rudsworth, Stanwell. She reluctantly accepted, and a year later discovered she had been cunningly deceived by Smith. Her new lease was less productive than Ankerwycke, so she took Smith to court [TNA C24/40].

The litigation is quite lengthy, but 2 aspects are worthy of mention. [TNA C24/40 and Eton Coll STA S3];

Firstly it was evident that "Sir Thomas Smythe found great fault with the estate, for part of the howseths weare not repayered as in dede they were in extreme ruyne and decaye…… the barnes and howses of Ankerwycke were in wonderfull decaie and ready to fall down, at past tymes…. That no one did any repayrs to it till it came to Sir Thomas Smith hands."

Secondly in defending his wife, the second husband of Joan, Michael Barrett tried to sway the outcome by saying the following about her: "Johan(na) Barrett is a poore and simple womang, halfbread and in Widowe destytute [destitute] of ffrendes” and requested the Jurors should take “pytie [of] the symplicitie and weakness of the said Poore widowe so muche deceived abused and ynpov(er)ysshed."

Whether or not these comments achieved the sympathy requested is not known, nor is the question whether Joan gave Michael a black eye!

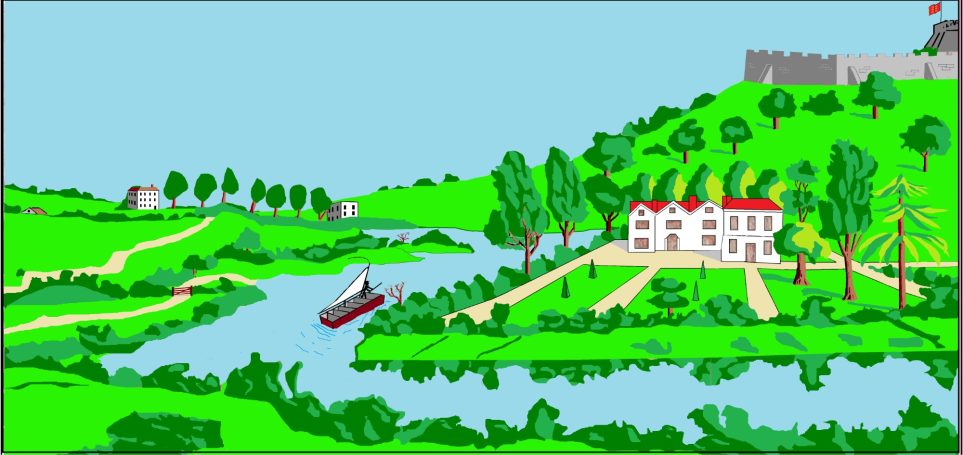

Artist impression of how Smith's mansion may have appeared. It was deliberately L shape, with both ranges facing the river, to give the impression of a much large house. The medieval barns were reused, but new stables and dovecote built adjacent to the new house. (c) Phil Kenning

1551-1553 Rebuilding of Ankerwycke

Smith quickly set about plans to redevelop Ankerwycke Priory. He kept a diary, and recorded the following:

1551 Et in huis annum fintio capi Ankerwick edificirratus

And at the end of this year building at Ankerwick

1552 Et toto hoc anno Ankerwick edificabat[ibus]

And also this year building at Ankerwick

1553 Alors isto a[n]no finis impositus est Ankerwici edifications

And finally and end in sight for building at Ankerwici

[British Library Mss]

No reliable images survive of Smith's mansion. However it would appear he was keen to demonstrate his learning, and travels in Orlean, France and in Padua, Italy. His interest in the renaissance was strong, but financially he was not well placed to create anything as magnificent as his close friend, William Cecil who later undertook monumental building works at Burghley. However it is much more likely Smith followed modern styles, perhaps trying to improve upon other Nobles / Courtier Houses such as Breamore, Doddinton, Shaw House or Farringdon Hall.

Smith incorporated a number of the original nunnery buildings in his design. It is known that the former Refectory occupying the south range, as well as the west range containing kitchens and lodgings were subsumed into the Tudor Mansion. Cellars were built within the lower floor of the priory. His great hall, later described as containing "loft windows" and measured 12m /40ft long [Cricket-Blake] and extended over two floors. Along the southern roof space a vast Long Gallery, about 53m in length was created. The intended purpose was to enable visitors to view his gardens from the top floor.

The facades of the house, however tried to attain high levels of symmetry, and this is evident in the geophysics which shows a line of symmetry extending right through the house and gardens, up as far as the Causeway bridge.

Archaeological evidence suggests also that he extended and elevated the site to reduce the threat from flooding, covering large areas with gravel (nearly 50cm over the foundations of the priory church, chapter house and cloister) and hundreds of tons of material to the south, that enabling him to create formal gardens. These I think were heavily influenced by his strong connection to France, and may be more similar in appearance to the great French houses on the Loire, such as Château de Chenonceau, Château de Chamerolles, Chateau de Gien or Chateau de la Ferte.

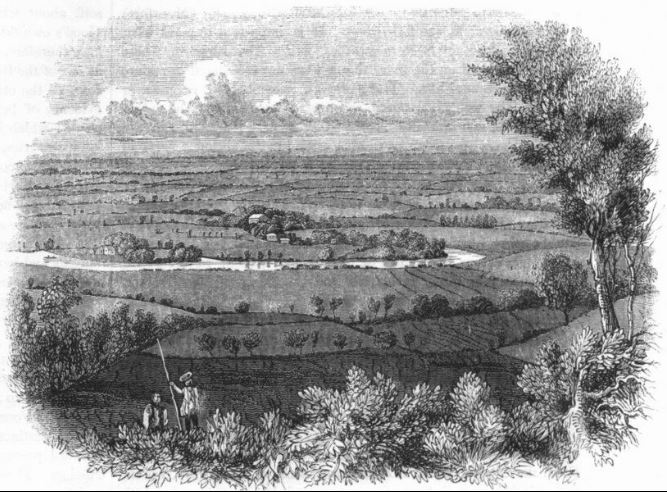

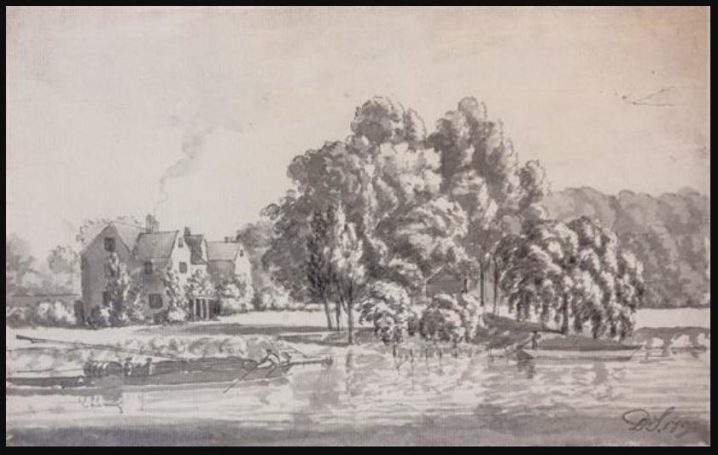

1604 Extract from Map DRO: DPOW 106 Dominic Serres c1799 Ankerwycke Priory Charles Warren Hankerchief (redrawn by S Burgess)

These three images are the only known ones that represent Ankerwycke. The 1604 Image, from a hand drawn map is the most reliable. It shows a representation of two ranges, with red tile roofs and dormer windows. The map is orientated facing west, so the view of the house is assumed to be looking at its northern facade. The image by Dominic Serres, used in Gyll's "History of Wraysbury, Ankerwycke Priory and Magna Carta Island" seems to show a series of disjointed buildings, rather than one complete 'new build'. Its lay out does not match the 1800 enclosure map plan, so must be viewed with caution. Lastly the Warren image was used on commemoration handkerchiefs at the Egham races in the 1790s, and is deliberately artistic to enable the purchaser to recognise the landscape. The left hand side of the building is certainly Tudor, but the right looks out of place, and there is no evidence for this in the Geophysics. Considering Warrens and Serre's images are close together in date, the buildings look very different to each other.

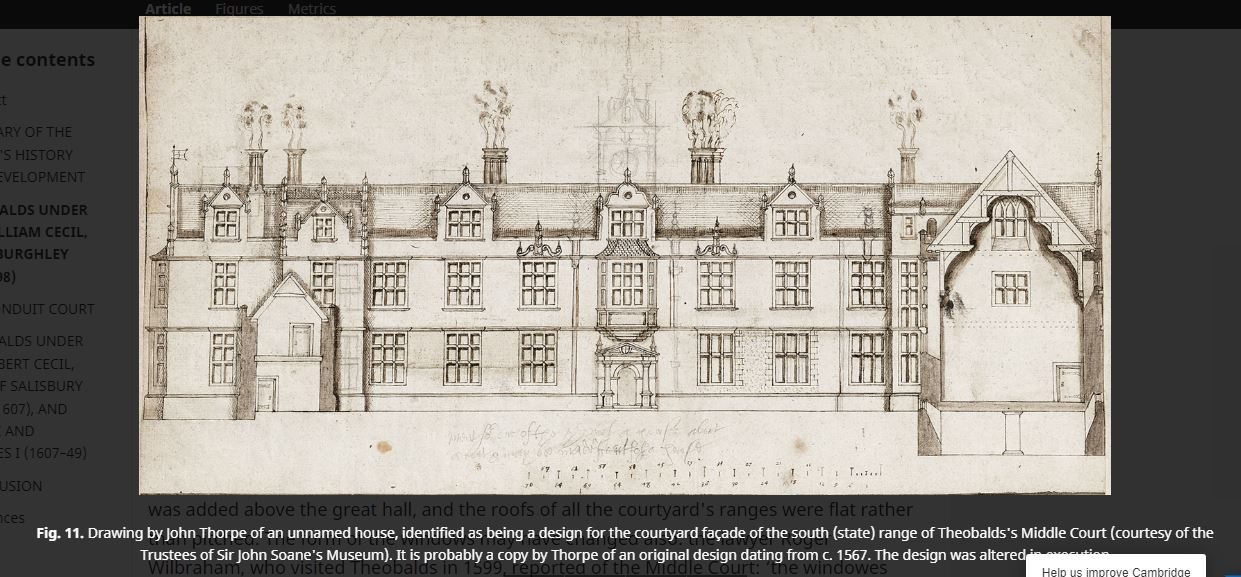

Despite a shortage of images pre 1800, there are some "un-named" buildings in various archives that could be Ankerwycke. The image below is one such image. Discovered in John Soans Archive, London, the building has to be a strong contender. Described as "The Garden side of an un-named house" its appearance fits very closely to map evidence (two projections facing south) and the notion of reusing medieval buildings (different gables on east projection, and a central doorway. However it has been suggested by Author Emily Cole that the sketch was a design for Theobolds Middle Court. I still would love to prove this could be Smith's Ankerwycke.

The symmetry is very strong, and the close link to William Cecil is also worthy of note: Cecil could have commissioned this sketch of Smith's House at Ankerwycke to enable him to copy elements in his house at Theobolds, Essex, which was built in the 1560s,

The fabric of the building was a mix of chalk, brick and stone. Details of the stone used for windows and door surrounds as well as fireplaces is derived from a report carried out by St Blaise Ltd in 1994 for Berkshire County Council. It suggests the Tudor building would have been a mixture of styles incorporating brick, chalk block and imported stone. Therefore it is highly likely Smith had the property limewashed to produce a uniform external appearance. Had he not, then the building may have looked more like Bisham Abbey (above), which Sir Thomas Holby altered in the same decade.

The variety of imported stone used at Ankerwycke suggests a large investment to obtain good quality building material suitable for carving and mouldings. With the exception of a Greensand that was used in a pointed trefoil window, the other stone was mostly related to Tudor features, and included:

• Oolithic limestone (16th century moulding),

• Cretaceous sandstone (upper east window from 1910 EW wall),

• Fine grain limestone (Ancaster hardwhite)

• Clunch (soft limestone)

• Carboniferous sandstone (2”x9”x5”) paving

• Ashlar stone (9.5”x 5”x6.75”).

The fabric of Ankerwycke

Large blocks of stone were transported to the site in both the medieval period and during the Tudor rebuilding. In a channel 100m from the priory are 4 large Reigate Stone blocks. They likely relate to Smith's period, and may have been surplus to requirements, utilised as a small bridge.

There is some conjecture that these stones are from a much earlier period, and could have been part of a Stone Circle called Nagen Stones, which were nine standing stones mentioned in a Saxon Charter, located just south of Staines upon Thames.

.

The mansion at Ankerwycke would have looked very impressive when viewed from the River Thames, but sadly Smith's Wife, Elizabeth Carquett never got to see the completed project. She was buried 3rd August 1553 at Wraysbury Church

Fortunately Smith was not lonely for long. He met Philippa Wilford who was daughter of Henry Wilford a London Merchant, and widow of Sir John Hampden (d Dec 1553). The following year, on 23rd July 1554 they were married, and Smith acquired the substantial Essex manor of Theydon Mount from his wealthy, childless bride. This meant Smith's would expect to travel between Ankerwycke and Hill Hall over the subsequent years However this was not to be the case, as upon his return to employment with the Crown, Smith was seconded abroad attending State business on behalf of Elizabeth I. This meant putting on hold any further building plans.

[Image is of Breamore House Hampshire, but image reversed to demonstrate how a 2 range house can still look large and impressive]

Previous Page : Medieval History Next Page: Elizabethan History

© Copyright. All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.