Lidar at Ankerwycke

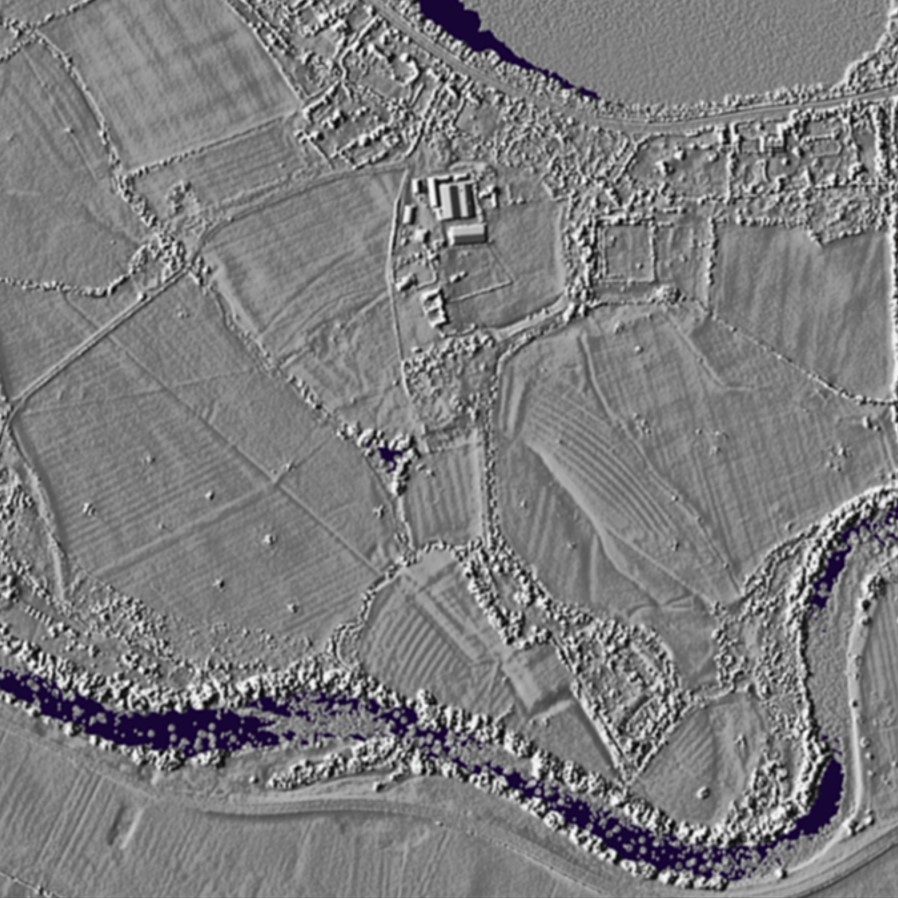

Lidar (Light Detecting and Radar) is a method where by terrain is measured accurately from equipment located in an aeroplane. As the craft flies over, every simple change in ground level, every lump and bump and any ditch or bank is surveyed in this way. The result of this is an image that shows the earthworks and other archaeological features in the landscape.

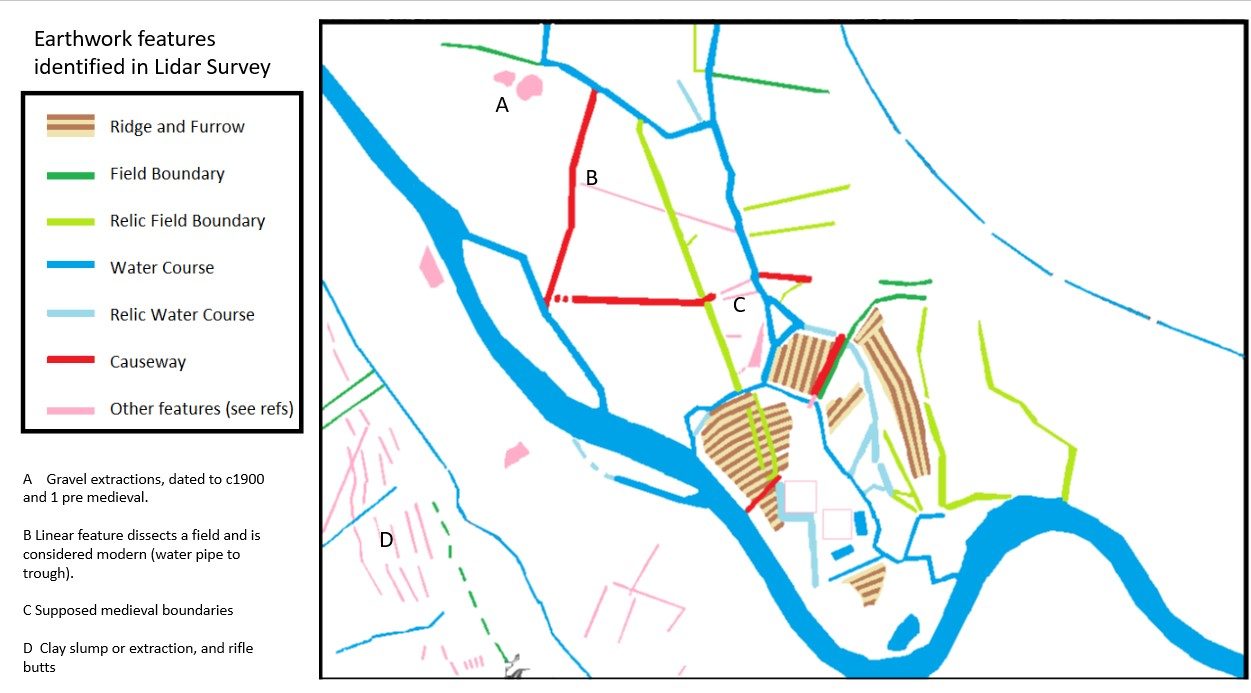

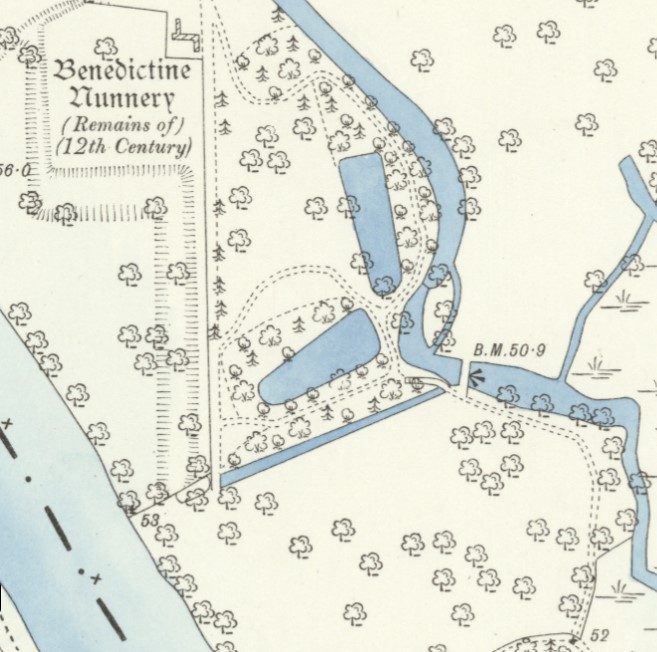

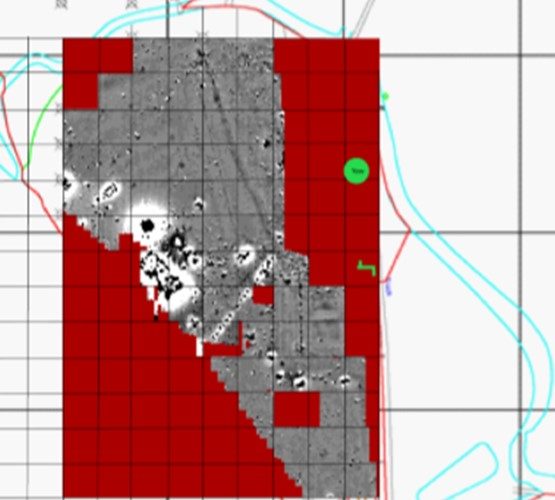

The image adjacent illustrates just how significant the land at Ankerwycke is. Features such as Ridge and Furrow, Causeways, Field Boundaries, as well as fish ponds and other water courses, are rare to find this close to London.

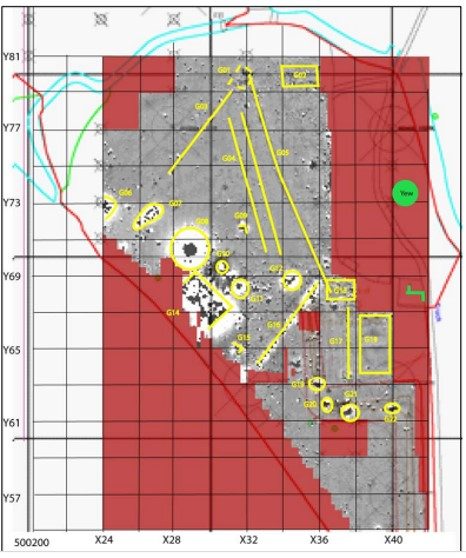

In the graphic below I have attempted to record some of the features. These are tricky to date without excavation. The other issue here is that this landscape is a floodplain, and earlier features or earthworks may have been lost due to inundation by silt and sediment. The relic watercourses are an example of this, because they have silted up and are more shallow and less defined.

Of particular interest are the Causeways. These align on thier west side to the river crossing of Ankerwycke Ferry. One causeway heads northwards into Wraysbury, whilst the other eastwards to the Priory, where it crosses a medieval ditch before reaching the medieval gatehouse.

The lidar does have limitations, however when this is combined with documentary research, excavation and applying the technique of landscape archaeology it is possible to reconstruct the various time periods at Ankerwycke.

Lidar Lying?

Compare Fig 1 and Fig 2.

In the Lidar scan a distinct circle of pits can be seen. I myself got very excited about this, as I genuinely thought it was evidence of a stone /timber circle! (I had my reasons - nearby are the Neolithic sites of Yeoveney Henge and Heathrow Circus).

However my joy was short lived when I checked the 25 inch OS to discover that there was an ornamental planting of trees recorded, but as these all had blown over, it left the root holes as earthworks.

Fig 2 25 inch OS map

Documentary Evidence

There are numerous archives that contain records pertaining to Ankerwycke. These include Manorial records such as Court Rolls, land transactions, suits and fines; there are also accounts and reports undertaken by the Bishop of Lincoln, during his visitations. Furthermore, leases by the Crown, private diaries and personal papers. all make for interesting reading. d.

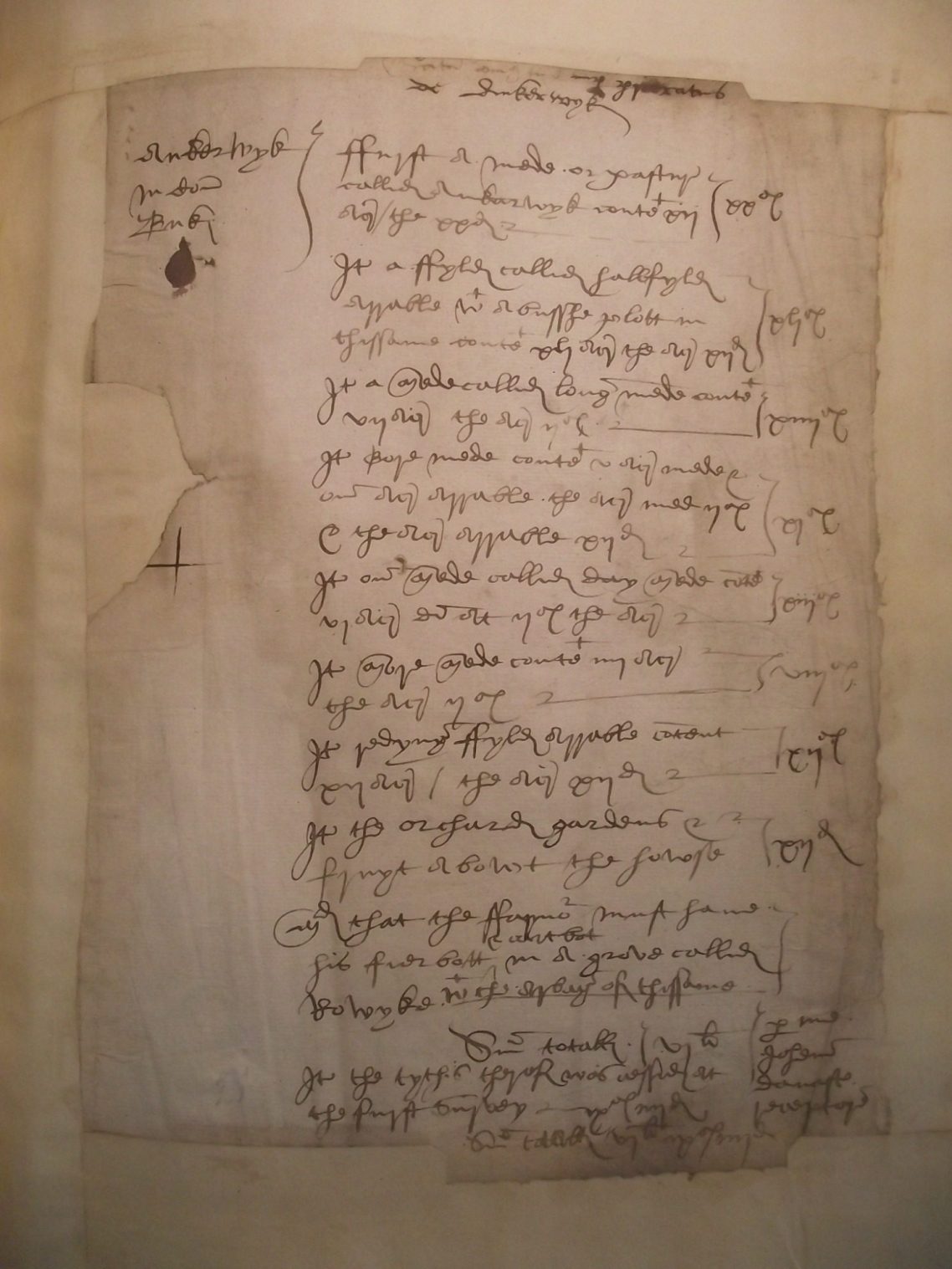

One of the more useful documents is from the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Recorded in the "Valor Ecclesiastica" are the surveys undertaken by the Commissioners set to value each monastery, abbey or priory. The text opposite reads as follows

- First a mede or pasture called Ankerwyk containeth xii (12) acres / (Valued at) 20d

- Item a ffyld called Hallfylde

arrable with a busshe plott in

the ssame containeth xli 41acres - Item a mede called Long(er) Mede containeth 7 acres (2sh an acre)

- Item Bore Mede containeth 5 acres mede and one acre arable

- Item one mede called Day Mede containing 6½ acres

- Item More mede containing 4 acres

- Item Redyng ffylde arable containeth 12 acres

- Item the orchard gardens and fruit about the howse

- All that the farmo(r) must have his fier bott and cart bott in a grove called Rowycke with the herbages of the same (ie grazing beneath the trees)

- Summa Total

Item the tythes thereof was assessed at the first survey 10sh 4d

Sum Totall £6 10sh 4d

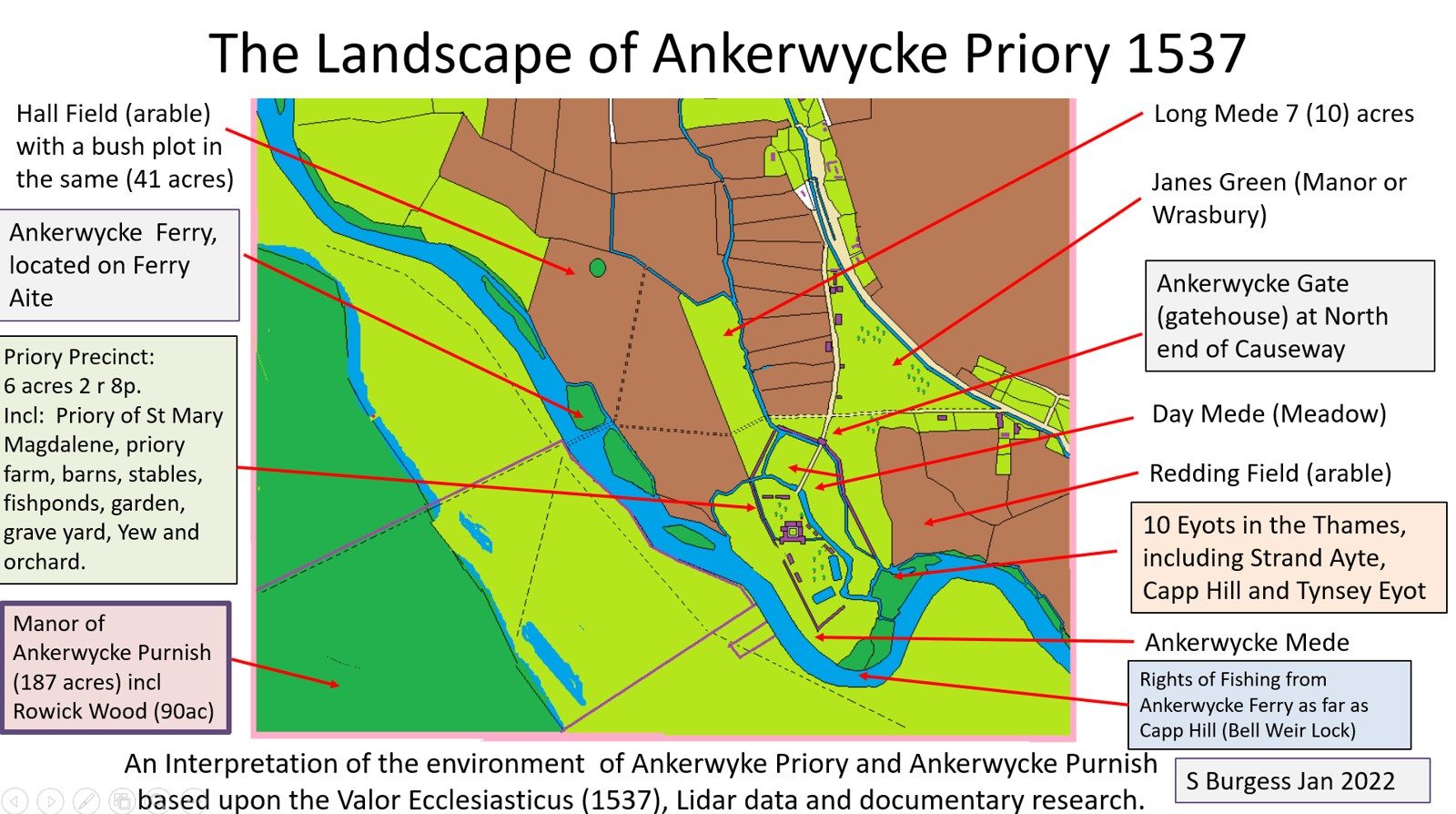

This information can be overlaid onto Lidar images, maps and plans to determine where these fields were, and how they were used. The graphic below is my attempt to show this.

By examining the Wraysbury Court Rolls, as well as other contemporary documents, the wider landscape can be conjectured. In particular it is very evident that the River Thames has barely moved over 1000 years. Indeed the only certain location where this can be shown is where the island is located in the midstream of the image. This island by 1700 becomes landlocked to the Surrey side, demonstrating a shift of the course northward. A similar occurence is also evident at Runnymede Bridge, where documents and parish boundaries show that the Thames flowed around the southern part of the island, prior to its modern course around the north side (Its south side now land-locked to the Surrey shore).

The image above shows a mixed farming community at Wraysbury. The large Open Fields on the higher ground to the east, and meadow adjacent to the Wraysbury Beck. Many occupiers were tenants of either the Manor of Wraysbury, or the Manor of Ankerwycke. They would have to farm the lands of the Lord of the Manor prior to farming their own. They had commoners rights to graze animals on the greens and commons, as well as take wood, hay and other produce from the land.

The precinct wall around the nunnery is mentioned in texts, however its line is hard to prove. Several references to 'Ankerwycke Gate' almost certainly would suggest the main gatehouse for the Priory. A second gatehouse is mentioned in 1441 (which was blocked up) perhaps suggesting access into the precint from the south? Hopefully further archaeological investigation will be able to shed light on its route.

Geophysical Investigations

In 2006 I was able to undertake a resistivity survey of the area of the ruins, yew and grassy platform to its south. The measures the resistance of a small electrical current through the ground between 2 probes. Walls therefore show up as areas of high resistance, The results were astounding, as can be seen.

The Resistivity survey, which for the first time identified a lost 16th century garden, that had been created by Sir Thomas Smith. It's geometric layout is strongly linked to his interests in the Renaissance and it is possible there was a statue or feature in the middle of the paths.

Interpretation of Results

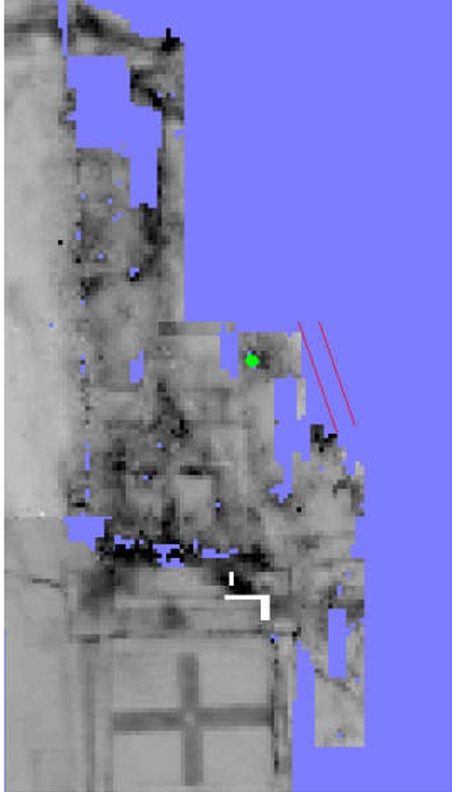

In the image above, the ruins have been highlighted in white, the blue areas are un-surveyed areas, and the green dot is the location of the Ankerwycke Yew.

It is possible to see a large number of foundations of walls and buildings. This will date from between 1160 and 1800, which makes interpreting them very subjective.

The most obvious thing to say is that the buried walls a mostly aligned on a N-S and E-W alignement. In the centre is an obvious square area (about 50ft /18m each side). This feature is almost certainly the central cloister. As most monasteries follow a similar layout, it can be speculated that the Church lie to the N of the Cloister, Chapter House, warming room and Dormitory (over) along the eastern side; Refectory on the southside, and kitchens and possibly guest/lay accommodation on the west. Map evidence confirms that Smith's mansion occupied the site of the Refectory.

To the south of the cloistral complex the grass platform south of the ruins is much less complicated: It clearly shows a criss-cross of 2 paths, which must relate to the Tudor Garden constructed by Smith in 1551-3.

To the north of the site, further buildings/ walls are discernible. These are difficult to interpret, not lease because of difficulties accessing the site due to trees and vegetation. Could these be part of the medieval farm, or inner gatehouse? Only excavation can answer this.

The 2019 Survey of Ankerwycke Mead by the Berkshire Archaeological Society was a very useful exercise

The large area of disturbance to the west is known from maps to be a swimming pool and changing rooms. However there are other more subtle features worth commenting about.

There is a diagonal line on a SW to NE alignment that heads to the Yew. This is a raised gravel path linking Ankerwycke Picnic to the Yew tree.

There is another anomaly - a dark linear feature running northwards through the site. There is a great deal of conjecture about this. It could be a modern drain or water supply to the swimming pool. Or it could be a medieval drain or conduit supplying water to the nunnery. I think it could be the western part of the priory precinct wall.

Recording the features found on the 2019 Survey of Ankerwycke Mead. Priory ruins and yew highlighted in Green

//

Archaeological Investigations at Ankerwycke

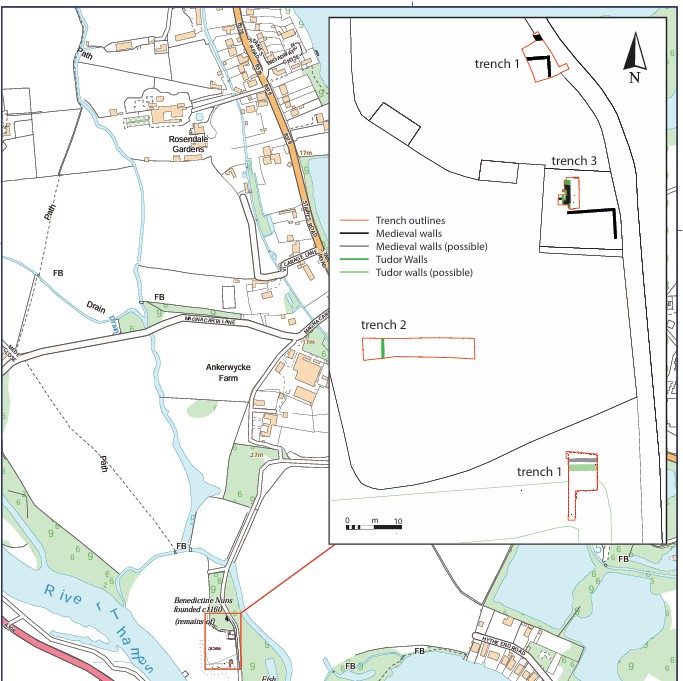

Over the past few years the National Trust, have undertook a large degree of investigative work, comprising geophysics, resitivity surveys and archaeological excavations to better understand the complex site. This culminated in 2022 and 2023 with the involvement of Surrey Archaeological Unit facilitating a community dig. Four trenches were excavated, and the results published in two reports. Below are the results from the 2022 excavation.

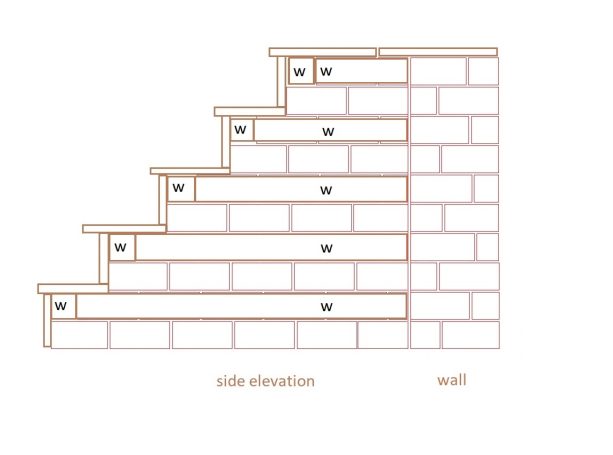

Trench 1 (images 1 and 2) show the excavation of part of the cloistral garth. THe right angle wall seen in image 1 would be supporting a timber structure that covered the walkway between the buildings. Image 2 was an extension to trench 1 which picked up the south wall of the priory church. The wall was over 1m thick, and was well faced on the internal side. The width of the walk way was 8ft (2.4m) and the conjectured size of the Cloister was 50ft (17.3m).

Trench 2 was located on the grassed platford south of the ruins. It identified the retaining wall built in the 1550s and alluded to demolition rubble nearby, perhaps suggesting a nearby building. The Tudor gravel path was very well compacted, and it was evident that the whole site had been deliberately elevated, partially as a means to avoid flooding, but mainly to create the geometic garden.

Trench 3 Adjacent to the ruins, whilst trench 4 explored the far side of the grassed platform. The excavation of trench 3 revealed that the Tudor building had indeed incorporated much of the surviving south range of the nunnery (Ie the refectory). However alterations had been undertaken to strengthen internal walls, insert fireplaces as well as create access to a cellar.

One of the most amazing discoveries was a short flight of steps that still contained timber fragments. This was built up against a medieval wall, and descended to the level of the original medieval floor level (near to it was discovered a threshold and doorway, worn by the feet of the nuns.

On the opposite side of the wall the trench revealed that an opening had been blocked with repurposed stone, and a fireplace inserted against the wall.

Runnymede Explored

For the National Trust Archaeological Records for Ankerywkce please click the link below:

2024

© Copyright. All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.