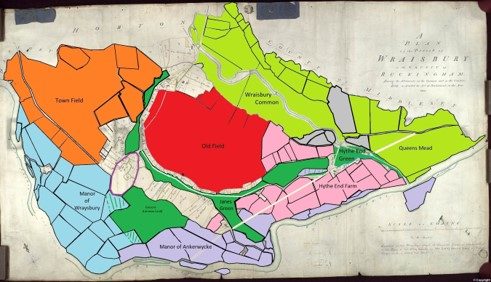

The demesne (or Lord’s) lands extended along the north side of the Thames as far as Hythe End. This land was valuable grazing land, solely used by the Lord’s flocks. The Montfichet’s owned four fisheries in the Thames, islands (known as Eyots) used to grow willow for basket making, and there were a parcels of woodland for 500 foraging pigs.

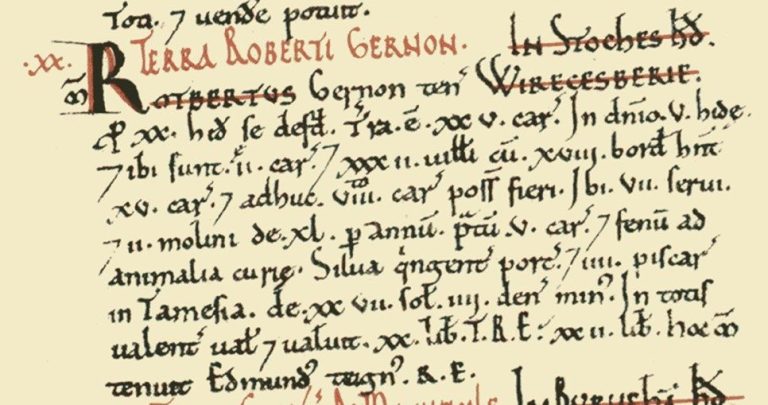

In 1086 the Doomsday Survey recorded the value of the Wraysbury lands. Robert Gernon was Lord of the manor.

In demesne [are] 5 hides ,and there are 2 ploughs; and 32 villans with 18 bordars having 15 ploughs, and there could be 8 ploughs more. There are 7 slaves, and 2 mills rendering 40 per year, meadow for 5 ploughs and hay for the beasts of the court. Woodland for 500 pigs , and 4 fisheries in the Thames rendering 27s, less 4d. In all it is and was worth 20l ; TRE 22l. This manor (lib[ertie]) was in the tenure of Edmund, a thegn of King Edward (RE – Rex Edward)

Doomsday Survey

In 1066 William, Duke of Normandy, became King of England. To reward his French Barons and followers he gave them lands and estates in England that were formerly held by Harold’s Saxon thanes. The Manor of Wraysbury, was previously held by Edmund of Childry, but at the accession of King William, Wraysbury transferred to Robert Gernon of Monfiquet, Calvados in France. The Montfichet mainly held lands in Essex, where they occupied a Castle at Stansted, renaming it Stanstead Montfichet.

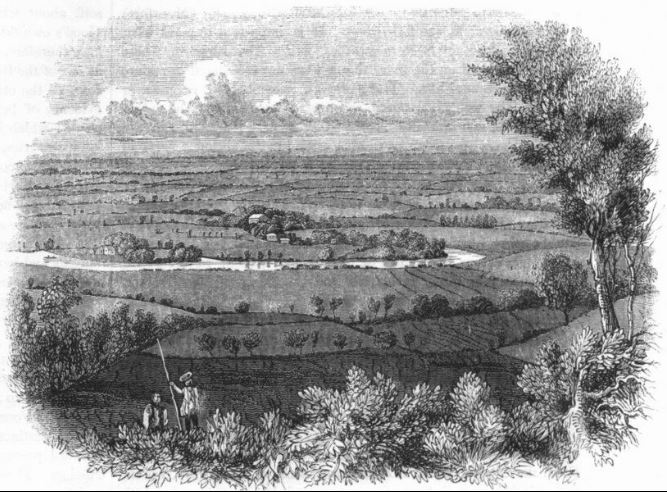

Their lands were managed under a system called Feudalism, whereby the King would own the land, and allow his barons to hold manors from him, proving him services such as knights, weapons, horses and provisions. Consequently the Montfichets would obtain income from their under lords and tenants, as Lord of the Manor, through holding Manorial Courts. Place Farm, Wraysbury is the likely location of the Manorial Hall. The Manor of Wraysbury itself comprised two large open arable fields, called Old Field and Town Field. Here villagers were allocated strips of land upon which they would grow their crops. Bond tenants would have to work the Lord’s fields first, prior to farming theirs. There were also large areas of common, adjacent to the River Coln, where villagers could cut turf, bracken and reed, as well as grazing their animals. Wraysbury also had three Greens, known as Wraysbury Green, High End Green (Hythe End) and Janes Green (adjacent to Ankerwycke).

The surname Gernon was dropped, and the family retained the name “Montfichet”. They showed their support to the King, and to God by giving pious gifts to the poor and undertaking important religious acts. In 1135 Robert Gernon’s grandson William (1090-1136) founded Stratford Langthorne Abbey. Located in West Ham, Essex, it was initially founded as a Benedictine daughter house to a French Savigniac house, before converting to Cistercian after 1150. His son Gilbert founded two religious establishments during the next decade: : Thrembal Abbey in Essex, for Monks, and Ankerwycke Priory for Benedictine Nuns here in Wraysbury. Furthermore he endowed further grants to Stratford Langthorne Abbey comprising of the Manor of Greenford, in Ilford.

The Nunnery he founded at Ankerwycke c1150 was endowed with a proportion of his manorial riverside lands in Wraysbury, as well “all assarted land” (ie cleared for agricultural use) previously held by Richard de Bruera.” A seal from 1194 shows what is thought to be the first church here, represented by a timber framed building, with a small central bell tower.

The legend on the seal reads “Sigillum Ecclesiae Sancta Marie Magdalene de Ankerwic”. Translated it reads “The Seal of the Church of St Mary Magdalene of Ankerwycke” [TNA SC13/R2]

Foundation of Ankerwycke c1150

Shortly after the foundation of the Nunnery, engineering work soon occurred at Ankerwycke. This was necessary in order to supply the priory buildings with a practical water supply. The Wraysbury Beck, that flowed through the estate in a south east direction was diverted to flow to the south west instead. A series of sluices were employed to then divide the new stream into several directions to supply the nunnery.

The former course of the Wraysbury Beck can still be seen as an earthwork in The Park, and holds water at times of flood (see image on Bronze Age Page).

Despite being on elevated ground, on occasions flooding affected the nunnery. In 1338 and again in 1394 flood waters severely affected the lives of the nuns, and they sought indulgence from the Bishop. However at this time the Thames was tidal as far as Staines (marked by The London Stone) which meant that the flow of the Thames would regularly back up and overflow its banks into the Floodplains of Runnymede opposite.

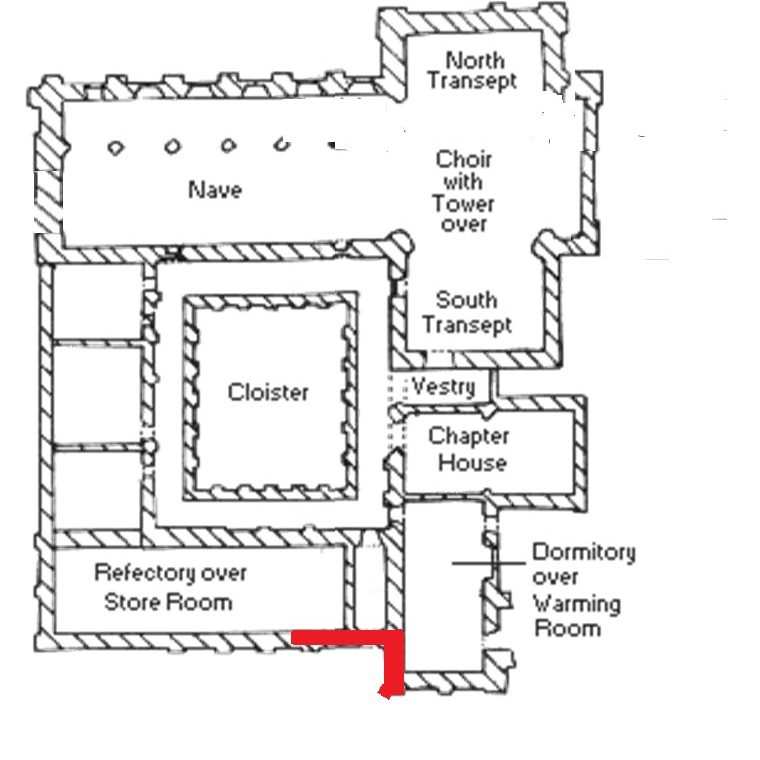

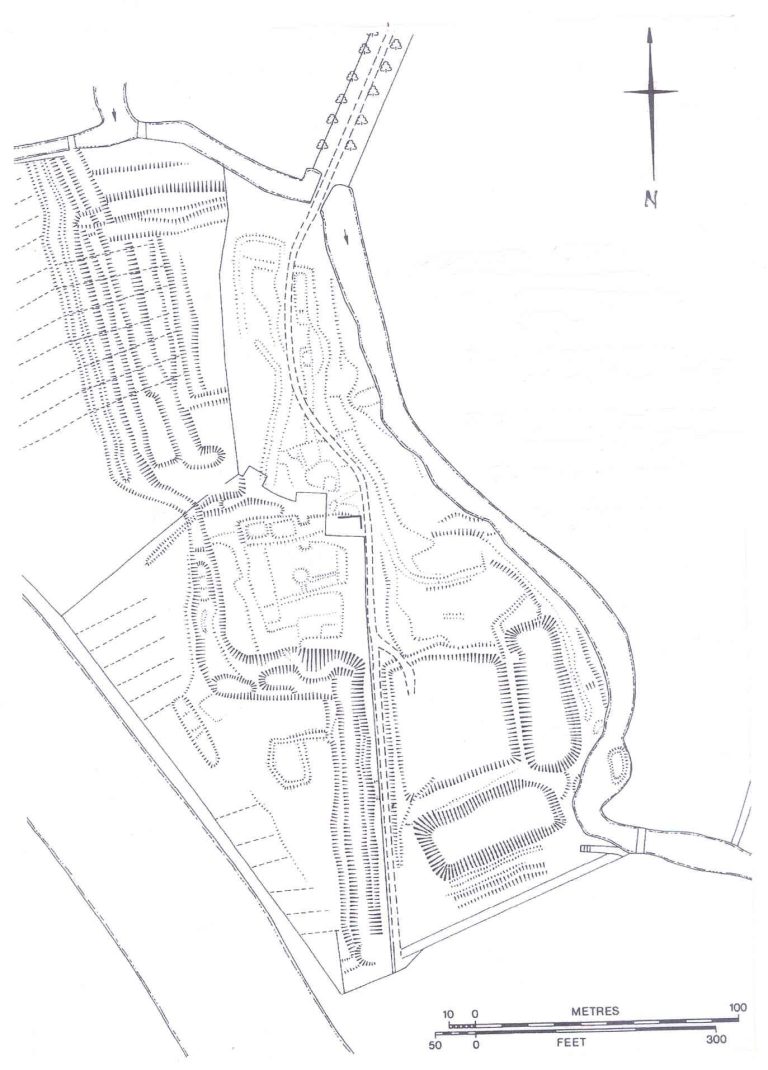

The plan above shows a typical simple monastic cloister. The red walls relate to the ruins visible today on the site.

Separate to the main Cloistral buildings was their farm, recorded to contain a Great Barn for storing the hay and tithes, another smaller barn, a granary, stables, sheep fold and pigsty. There would also be a brewhouse for making beer, and bakehouse for the bread. There may also have been an Infirmary for elderly or unwell nuns elsewhere on the site.

To the south of the priory complex were two fish ponds, which were used to store fish. Indeed fish was the main diet of the nunnery, and they owned “all the fishing in the Thames from Ankerwycke Ferry to Capp Hill” (Magna Carta Island to Bell Weir lock today).

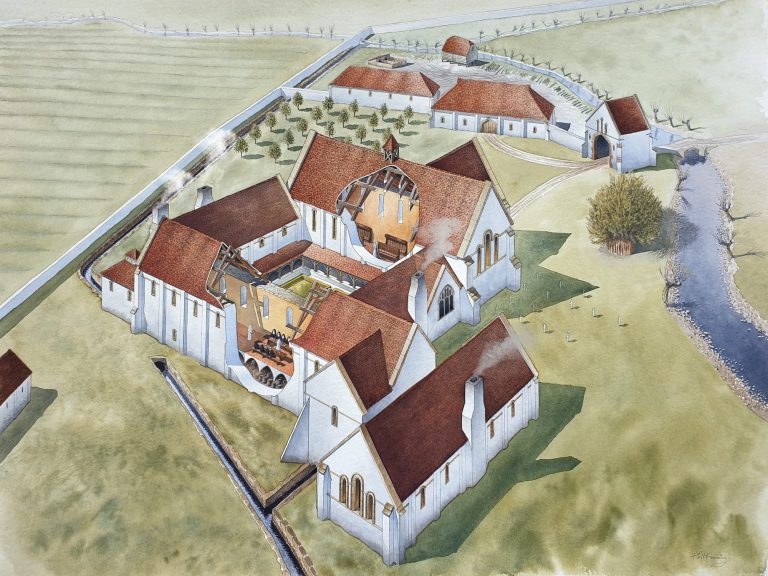

Above: Artist impression of the Priory buildings at Ankerwycke. The buildings were arranged around a 17m square cloister. The north side was occupied by the Priory Church. East range consisted of Chapter House, warming room and night stairs, that led from the dormitory above. The South range comprised the Refectory where the nuns ate. It was located above barrel vaulted cellars. Adjacent to the east was the latrine block, and perhaps too an Infirmary. The west range included kitchens and guest lodgings. Art work by Phil Kenning.

The plan above shows the nunnery occupying the island. The land immediately around the priory buildings were enclosed with a precinct wall and gatehouses controlling access to the nunnery. One gatehouse was located to the north of the precinct, at the top of the causeway adjacent to Janes Green where the poor would assemble to be given alms by the nuns. The gateway also allowed carts carrying the tithes (10% of local produce) access as well as other visitors and travellers would be accommodated at the Nunnery. A second gateway controlled access to the inner precinct and it is conjectured this was located at the southern end of the present causeway.

Within the precinct was the Priory Church of St Mary Magdalene. Geophysical surveys suggest it may have contained one aisle to the north, as well as several chapels. There was a cloister to the south, with the east range comprising Chapter House, Warming House and Dormitory, South range being Refectory and west range containing kitchens and guest lodgings.

The plan adjacent shows the earthworks found at Ankerwycke.

To the north, the main water course enters the site, where it is deliberately channelled. Sluices would have been located at this confluence to regulate water flow as desired. Only the east- west ditch is obvious today, however it is likely there was a conduit heading directly south that was buried. A linear anomaly is discernible on the geophysics, alluding to a feature that relates to a conduit (or perhaps Precinct Wall)

This southward conduit, built in stone, supplied the nunnery with water for the kitchens and latrines. The east channel fed the fishponds, whilst the westward channel perhaps acted as a relief channel (or possibly fed a watermill?). All the channels drained into the Thames.

There is a central earthwork that is likely medieval in date and presumably relates to the transport of the chalk blocks and materials to build the nunnery

Other features seen on the plan include ridge and furrow, caused by ploughing, and other linear earthworks, perhaps caused by livestock movements and ground disturbance. (See Archaeology page for further details)

Lands and Estates of Ankerwycke

During the early decades of the Nunnery’s history, their land holdings increased locally, with the sons and grandson of Gilbert de Montfichet (both called Richard) giving lands to the nuns in Alderbourn, Langley Marsh and Wraysbury. Here, further property included an island in the Thames called Tynsey Eyot, fields called ‘Wymede and Morelaund, and a weir, house and 15 acres of land’ elsewhere in the parish.

Other pious gifts followed, with the nuns receiving lands and property in Essex, gifted by underlords of the Montfichets’ in Mauden and Takeley, as well as estates in Greenford, Stanwell, Langley and London. The latter properties included tenements in Fleets Street, Aldersgate and Fishstreet.

One of the Nunnery’s largest estates was on the opposite side of the Thames. It was originally called Westdrew Purnish, and later referred to as Ankerwycke Purnish. Eventually comprising 190 acres the sub-manor was given to the nuns by Chertsey Abbey, who were Lords of the Manor of Egham. Comprised of mostly a hazel and oak woodlands, and called Rowel / Rowick, Anchoress Wood [known after 1537 as Kings Wood] and Gulden Half Acre, it was managed for coppice wood for making hurdles, wattle and fuel. The standard oaks were cut for building, and the open areas grazed with sheep. A further area of land had been enclosed from Windsor Forest for the pannage of pigs.

By 1400, the nunnery possessed 1157 acres of land and 15 properties as well as 60 acres of waste in Windsor Forest. The income derived from this would have been plenty sufficient to maintain the nuns, and yet in Court Cases around that time, they styled themselves “The Poor Nuns of Ankerwycke” – presumably to gain favour at Court, rather than actually representing their financial position.

VISITATION OF BISHOP ALNWICK

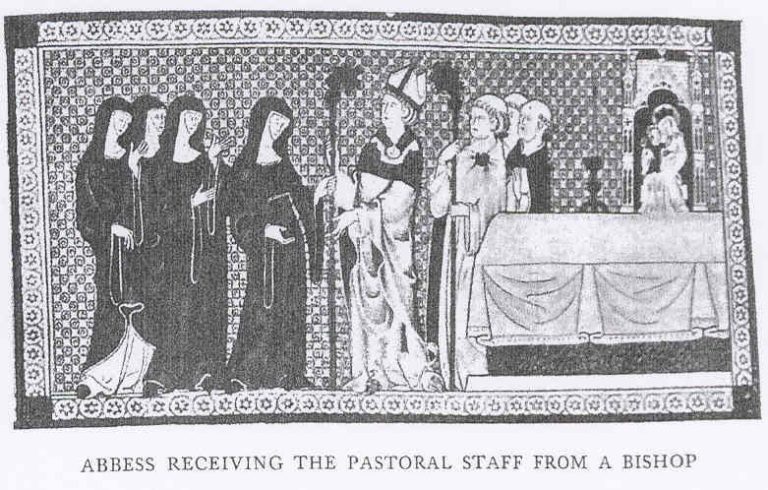

The Benedictine Nunnery was managed by the Diocese of Lincoln: Bishops would regularly travel to assess the condition of the monasteries and priories in their jurisdiction.

Known as the Visitations, Bishops would take stock of any issues, instil obedience and resolve problems. Two such visits are documented in the Diocese of Lincoln Archives. The information provides us with a fascinating an important insight to medieval life at Ankerwycke.

In October 1441 Bishop William Alnwick came to Ankerwycke and found things at the Priory in a bad way:

The meeting occurred in the Chapter House. Bishop Alnwick and his attendant, along with 10 nuns. The Bishop interviewed the nuns, directing questions at both the Prioress, Clemence Medford, the sub-Prioress Dame Isabel Standene and the Cellaress Margery Kirkby. However three young nuns (novices) all aged under 13 were not questioned.

There were many points to discuss, and complaints were numerous, mainly directed at the Prioress, some about the priory, but many directed at her treatment of the other nuns and he bending the rules. For example:

It transpired that Clemence Medford was entertaining her friends and guests at the Priory's expense. She was accused of "bringing into the priory divers strangers and unknown folk both male and female, and maintains them at the common cost of the house, and makes nuns of some that are almost witless and others that are incapable".

She was accused of wearing silks and furs as well as jewellery, which was against the Benedictine Rule. "She wears golden rings exceedingly costly with divers precious stones, and also girdles silvered and gilded over silken veils, and she carries her veil too high above her forehead".

However the Prioress responded that the nuns did not obey here, and they themselves were breaking their vows of silence, “talking to men in the openings that faced Thamesward”, which she’d recently blocked.

With regard to the buildings and possessions, things were being mismanaged and in some cases buildings were in a poor state of repair:

She caused timber at Rowel (Rowick Wood in Ankerwycke Purnish) to be felled at unseasonal times, "suffering the boughs to remain after felling, by reason whereof it is not likely that the wood will grow again".

There was a lack of serving folk in the brewhouse, bakehouse or Kitchen, so the nuns had to not only prepare the food, but serve as well; The novices lacked suitable instruction for want of a teacher (governess /informatrix).

If that wasn’t bad enough, the Bishop was told that “hay was stored in the Church for want of barns”, because the sheep fold and hay barn had burnt down some years previous and had not been repaired. A gate way was blocked up “through which needful stuff was bought in, and peas pods and other draff carried out…and now all things were carried through the church to the great scandal of the house”. Consequently “beasts (likely pigs) would befoul the cloister.”

The Cellaress, Margery Kirkby, who later was appointed Prioress, after Clement's death in 1443, continued with the complaints: stating that the conventional buildings were going to wrack and ruin and though the house had received monies to pay for the repair, the Prioress was spending money on herself and entertaining guests.

You can read the whole article here from the Lincolnshire Records Society 1918 :Visitations of Religious Houses in the Diocese of Lincoln. Vol 2 (pp 1-9).

The Nunnery were gifted free fishing in the Thames from Ankerwycke Ferry (above) to Capp Hill- a distance of nearly 2 miles. Extensive research has determined that the Fishery extended from Magna Carta House (the location of the medieval ferry) down stream as far as Bell Weir Lock today. Salmon, eels, bream, rudd and carp would have been fished, and either stored in the priory fish ponds, or sold at market.

The Ferry was necessary for the nuns to access their lands on the Surrey side of the river. Here they held the Manor of Ankerwycke Purnish. This encompassed over 160 acres of land that today forms part of Coopers Hill Woods and the adjacent land now located behind the Magna Carta Memorial.

In addition to income from rents from their lands, the Nunnery derived income from borders, travelling guest, and wills. For example in 1375 William de Bathe of the Parish of St Bridget, London bequeathed: "to Alice, prioress of Ankerwycke, I leave a tenement in Shoe Lane, on condition that the nuns maintain a Chantry for the good of my soul…… and "to Matilda [his daughter] certain rentes of a tenement in Flete [London], with remainder to the nuns of Ankerwycke for clothing etc”.

In 1445 Sir William Estfield, Mayor of the Staple of Westminster, bequeathed a gift of half the rent from a tenement to the nunnery, the other half being gifted to Westminster Abbey.

Archives also record the wedding in 1280 “at the Door to the Church Ankerwycke Priory of Geofrey de Pycheford and Alice of Drayton. [PRO Close Roll 8 Ed1]. It cannot be a coincidence that the Nunnery owns land in Drayton shortly after this date.

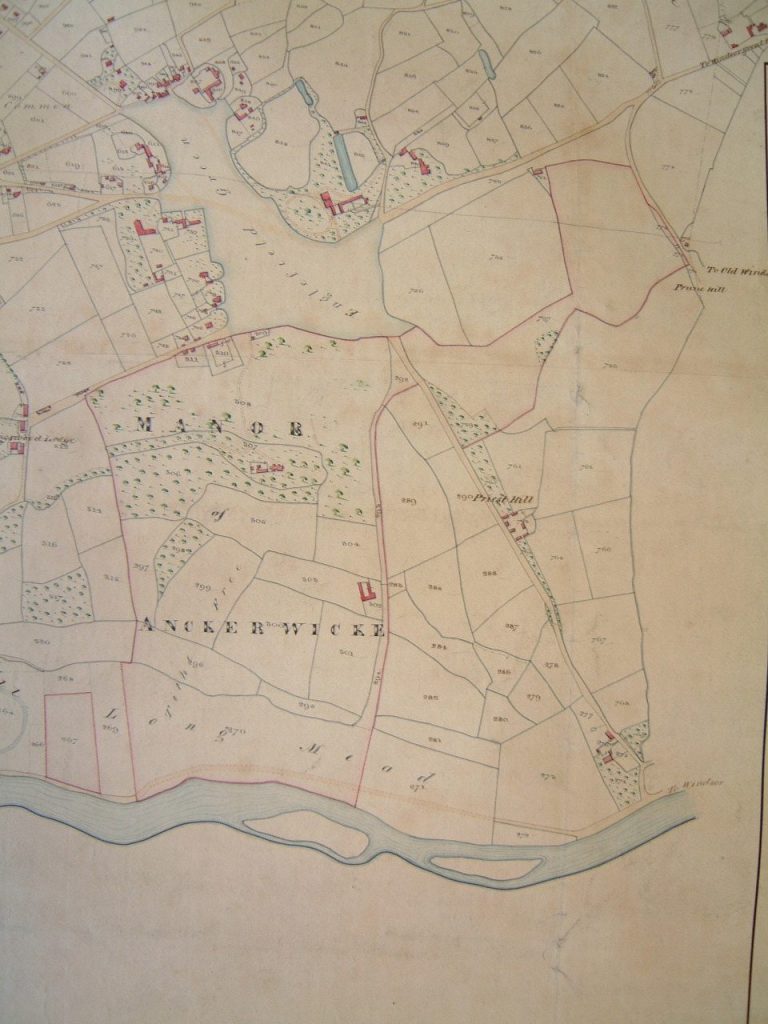

This Map, c1860 orientated with north to the right shows the land formerly held by Ankerwycke Priory. [Surrey History Centre].

Historically this land comprised open common land on Long Mead, as well as the steep wooded hillside. They only owned a small wood in Wraysbury called "Grethege", so the Purnish woodland was an important possession. The nuns held manorial courts there, and their tenants managed the land in exchange for tenements and farmland. Further land was given by Henry III in the form of waste land in Windsor Forest, in which the pigs of the nunnery would be taken, to feed on the acorns and beechmast in the autumn.

Today the steps up to the JFK memorial mark the northern boundary, whist the steps up to the Air Forces Memorial, just past Writ in Water demark the southern boundary. Vast veteran Oaks line these boundaries still today, which exist as obvious ditches and banks.

“Men would talk to the nuns through the narrow openings that faced Thames-ward”, to which end the windows there were boarded up".

Henry VIII Dissolution

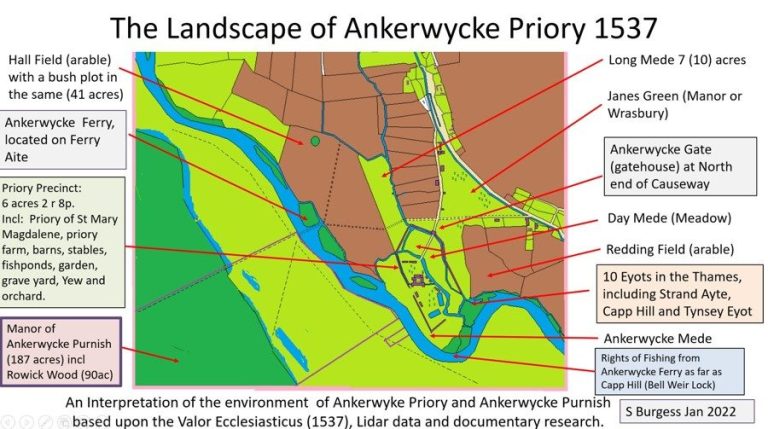

In 1536, when Henry VIII took the bold decision to break away from the Catholic Church and become Head of the Church of England, it resulted in the loss of the abbeys and priories. Known as the dissolution of the monasteries, the King’s surveyors were sent to assess the land and value the possessions of each. The Valor Ecclesiastic (church valuation) records all the lands at Ankerwycke, and enables us for the first time to conceptualise the landscape in the 16th century.

- First A mede or pasture called Ankerwyk containing 12 acres

- Item, A field called Hallfylde (arable) with a bush plot in the same containing 12 acres

- Item, A mede called Long Mede containing 7 acres

- Item, Bore Mede containing 5 acres mede and one acre arable

- Item, One mede called Day Mede containing 6½ acres

- More mede containing 4 acres

- Redyng fielde, arable, containing 12 acres

- Item the orchard gardens and fruit about the howse

- All that the farmo(r) must have his fierbott and cart bott in a grove called Rowycke [Ankerwycke Purnish] with the herbages of the same

Summa Totalls

Item the tythes thereof was assessed at the first survey 10sh 4d

Sum Totall £6 10sh 4d

After the priory was closed, it remained in the hands of Henry VIII. The last prioress, Magdalen Downes received a pension of £5 annually, and married an Egham man, who was servant to Edward Windsor, constable of Windsor Castle.

The map above of the Ankerwycke Landscape is based upon the 1537 Survey as well as evidence from Lidar and documentary research.

The bush plot mentioned in the survey relates to a former gravel pit. The fact it is redundant in 1537 suggests it has not been in use, but may date from the 12th century or even Roman times.

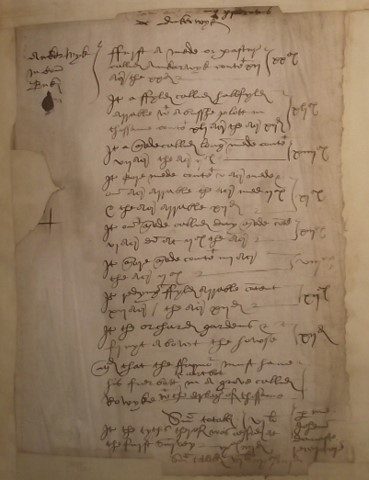

Below is the survey undertaken in 1536. The Commissioners for Henry lists each of the fields within the demesne of Ankerwycke in Wraysbury, describing them according to their state of cultivation, size and value. [TNA E315/402]

From a research point of view it is of immense use, as for the first time it is possible to relate the field sizes to known earthworks and features in the landscape.

Indeed it is possible to use modern maps, lidar images and documents to reconstruct the medieval landscape. This is a rare thing, especially when it is considered how much change has occurred since the medieval period.

Of greater importance, is that as the estate enters a new phase, it becomes easier to understand some of the changes made, and recognise them in both the landscape and in archaeological contexts.

Previous Page : Early History Next Page: Tudor History

© Copyright. All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.