Smith's House comes under attack

On the accession of Elizabeth's I in 1558 Smith returned to public life, becoming a Member of Parliament for Grampound, Cornwall, and holding the office of Ambassador to France. He spent much time away from Ankerwycke on state business. He was rewarded for his services, and given the lease of Wraysbury Manor and later Remenham Manor (a sub-manor in Wraysbury).

On 8th November 1559, whilst Sir Thomas Smith was in London, his property was seized by the sons of Andrew Windsor, the previous lease holder at Ankerwycke. His descendants disputed Smith's claim to reside at Ankerwycke, stating they had right of 'Tail Male' and that they were entitled to the hold Ankerwycke upon the expiration of the 21 year indenture of lease issued to their father, in 1538. Edmund Windsor, Esq., of Stoke Poges, Buckinghamshire, one of the Knights of the Carpet (1553) and Thomas Windsor, of Bentley, Hampshire, were later examined at the Court of Star Chamber, from where we are enlightening us with this account[TNA STAC 5/S25/17 & STAC 7/15/3]:

The brothers arrive between eight and ten in the morning, accompanied by twelve "ryotous and evyll dysposed persons". The men are armed with bucklers, swords, billets, knives and arrows. They "ryotously and forcybellie and in a most ryotously manner" evict Smith's servants and some of his possessions from the buildings . They take hold of the key, board up the door to the mansion and prevent the servants re-entering the property. Word is conveyed to Smith, who rides back from London, arriving at six the same evening. He is accompanied by a constable from Wraysbury, with his servant, and successfully repossesses it.

What is of particular note is that Thomas Windsor gives his account of the events of that day, which give details regarding the buildings that Smith owned at Ankerwycke:

"One of his servante and two of Edmund's servants…be left behind…to contynew and kepe the possessions….The said servantes so lefte were appointed in differente and severall places, that is to say one of them in the mansyon howse, another in a howse called the warren(ers) howse, the third in another of the ante howses builded upon the said scite."

One of the most curious things to draw from the records is the mention of the Warrener’s house, and where this might be. One suggestion might be that the Warren House is not near the Mansion, but elsewhere on the estate: Indeed the medieval field of Hall Field NW of the priory, located adjacent the Thames was divided and renamed Upper Warren and Lower Warren. Midway along the western boundary, is a 3 acres island, formerly Ferry Eyot, and now known today as Magna Carta Island. If Smith deemed the ferry crossing redundant, what better use of the island than for breeding rabbits. They'd be no need of a fence, as rabbits (and foxes) are reluctant swimmers and unlikely to escape. Whether this warren was established by Smith, or already present during the time of the nunnery is not known, But it was not uncommon for gentry to rear rabbits, as well as hunt with falcons, and what safer place than on an island, where they would not escape.

The only other logical place for the warren is on high ground, which would more likely be in the vicinity of the fishponds, but it is not known how far Smith's gardens and pleasure ground extended.

Smith, Cecil and Elizabeth

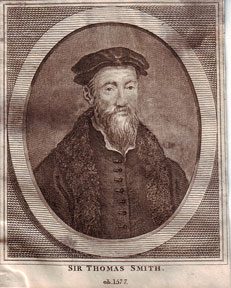

Sir Thomas Smith's life is well documented by Mary Dewar and John Stripe, and further information can be found in the Links Page.

Sir Thomas Smith's intellectual abilities were well known to the new Queen, Elizabeth I. His work on the Book of Common Prayer, and his tactful management of affairs surrounding the fall of Somerset, demonstrated Smith's skills and capabilities.. Advised by William Cecil, one of Smith's closest friends, Elizabeth employed Smith as Secretary of State for France in 1562 and he became one of Elizabeth's most trusted Protestant counsellors, remaining in France for long periods, dealing with diplomatic affairs there.

William Cecil appointed Smith to the Privy Council, where he was an influential counsellor and spoke on the Treason Bill and other matters. His outstanding work elevated him to the higher ministerial echelons and in 1572 he was appointed Chancellor of the Order of the Garter and in July the same year, Principal Secretary.

The Royal Progessess 1565

Queen Elizabeth is recorded to have visited Smith's house at Ankerwycke on 8th August 1565 [Mary Hill Cole, The Portable Queen. P82]. Unfortunately Smith was abroad in Nantes, France. However, he wrote about this later that year, in a letter to Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, stating:

"That it pleased the Queen’s Majesty to take my poor house at Ankerwick I am most glad, but sorry that it was not mine and my wife’s also good fortune, that my wife should be there at that time after our rustic manner to entertain her Highness. Marry that your honour writeth that her Highness was merry there recompenseth all. And I pray God I may once see her Majesty merry there, and your Lordship together.

Then I shall reckon my house twice sanctified and blessed".

Smith greatly plays down the status of his house, referring to it as "my poor house". I think poor in this case just refers to 'lesser'. Maybe he was not expecting Elizabeth to ever use his house. Yet, as will be seen below, it had sufficient grand apartments and rooms befitting of a Queen.

It was not uncommon for the monarch to utilise their subjects houses, when on the annual royal summer progress. Indeed it is often recorded that owners of houses would ready their mansions to accept her by undertaking extensive works. This clearly was not the case at Ankerwycke, yet the house was clearly of suitable size to receive the Queen and her retinue. For many courtiers it was mixed blessing to host the King or Queen. On one hand it was a great honour to accommodate royalty, however on the other it came a great expense: Food, entertainment and in some cases building new ranges and lodgings no doubt caused financial difficulties for some.

This was the case for Loseley Park near Guildford (below), which faired very differently to Ankerwycke. The Tudor house, owned by Sir William More was declared 'not adequate' by Elizabeth in 1562, and she requested something larger be built. Thus between 1563 and 1569 a more befitting grand house, with stone from the ruins of Waverley Abbey was built to accommodate the Queen. However despite all the grand works, Elizabeth upon arrival requested to stay -not in the grandest chamber- but in a small, north facing room, draped in tapestries.

Elizabeth's visitation to Sir Thomas Smith's house may be the missing piece in relation to one of the historic stories associated with Ankerwycke.

Many readers may be familiar with stories surrounding the Yew being the location of Henry VIII courting Anne Boleyn. But what if the oral commentaries over time altered, and changed from Queen Elizabeth meeting Sir Thomas Smith in 1565. It could be easily conjectured that over a few centuries, the inhabitants of Wraysbury began conversing about a female, a monarch, and a meeting at Ankerwycke. In this case, the female and the monarch are one and the same (ie Elizabeth). Plus coupled with the link that the Manor of Wraysbury was in Royal hands and formed part of the dower of Katherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn and Jane Seymour. Suddenly it is not beyond the realms of possibility that an apocryphal story about Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn develops.

Inventory of Rooms at Ankerwycke 1569

Was Smith's house large enough to accommodate Queen Elizabeth?

The answer would have to be yes.

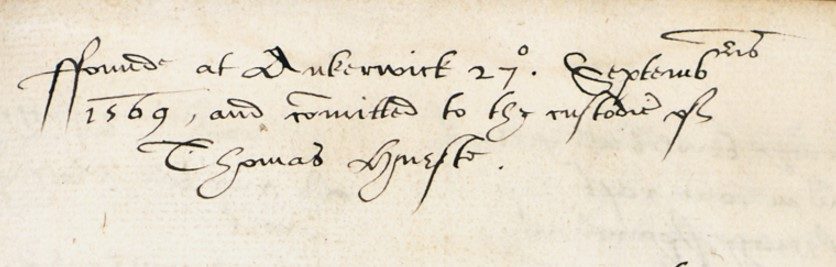

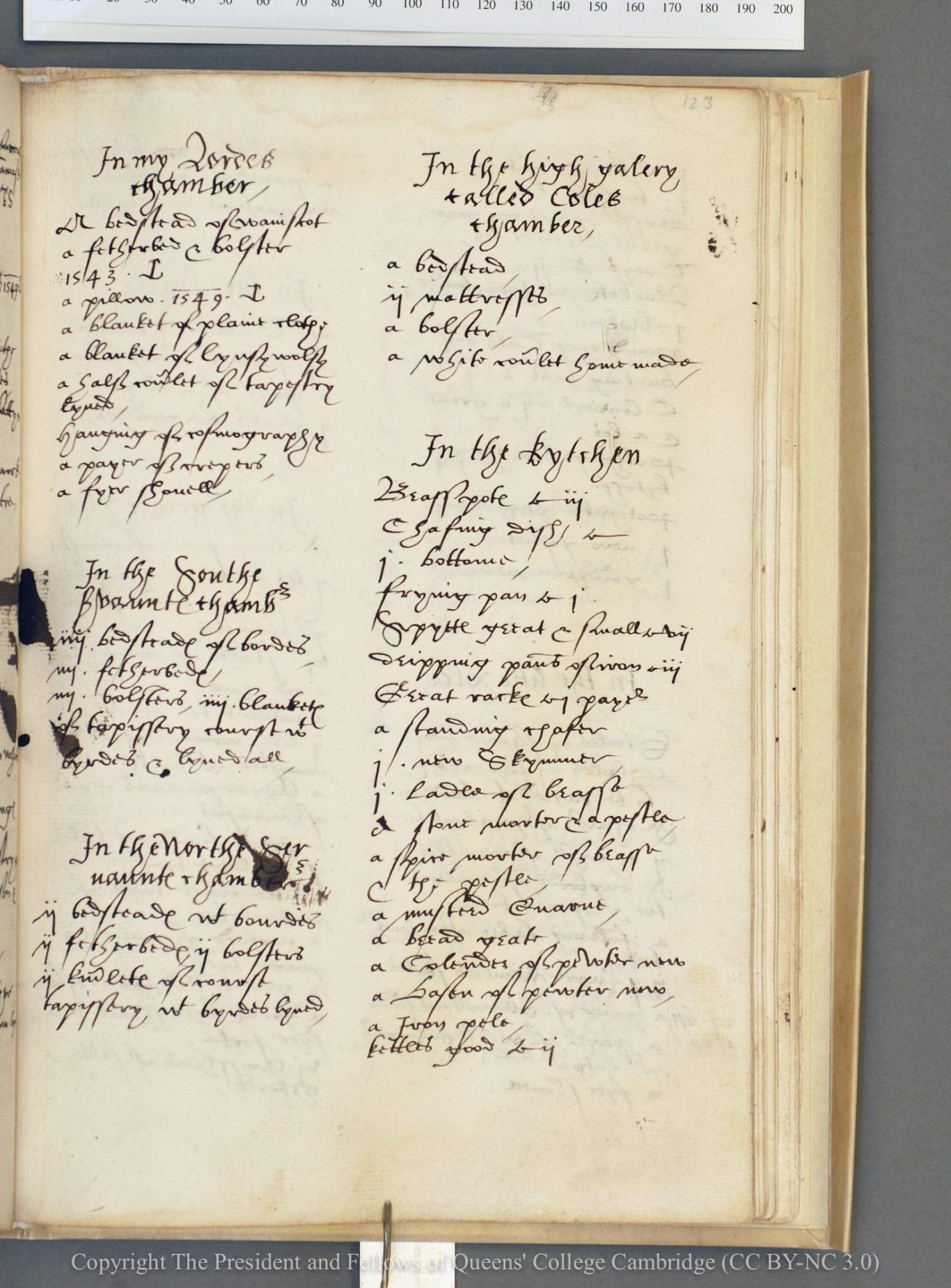

Several useful sources of information exist which enable the reconstruction of house. The most valuable source of information is from a surviving probate inventory taken at Ankerwycke in 1569 [Brit Lib MSS Queens 83]. It lists 23 rooms, and provides a very useful insight into the arrangement of the house as follows:.

The maydes chamber

Without the chamber in the corner of the priory

My wife's closet

My owne chamber

The Chamberlaynes chamber

The half part to the great Chamber

The great Guest Chamber

The inner chamber to the same on the south side

The north inner chamber

My father’s chamber

My lords chamber

The south servants chamber

The north servants chamber

The high gallery called Coles Chamber (also Coles Gallery)

The Kytchen

The little parlour

The hall

The great parlour

The chapel

The buttery

The wardroppe

The Lodge

The long house

At least 13 windows on the upper floors are referred in the document to as well as 7 fireplaces. Some of these rooms were furnished to very high standards. Mention is made of a number of rooms that were hung with tapestries, including one depicting the history of Samson and Susanna, and others made from damask.

Image available online. Queens College Archives Queens 00083-000-00251 Fol 121

Sir Thomas Smith of Ankerwycke and Hill Hall, Theydon Mount, Essex

Returning eventually to Theydon Mount, Smith commences extensive building work at Smith's Hill Hall estate was undertaken between 1569 and 1575. PJ Drury, P.(1983) has shown that Smith extensively remodelled the four ranges around a central courtyard, adding elaborate, renaissance details to the inner façade, and vast columns to the exterior. One surviving façade still has its 3-storey projecting towers, each with heavy entablature supported on giant Doric half-columns The internal façade of the courtyard is relatively unchanged from the 16th century: It comprises of 2 storeys with superimposed Doric and Ionic orders. The windows are mullion and transom except on ground floor of south range where once an open logia or arcade existed adjacent to the Great Hall. A four-centred entrance doorway in north range, flanked by columns supporting a pediment demonstrated to all arriving that Smith possessed extensive understanding of the Renaissance.

Internally, his ideas and tastes continued, and the crowning glory of the house has to be its wall paintings: The north range contains wall-paintings of c1570 depicting the story of Cupid and Psyche, scenes from the life of King Hezekiah, a contemporary aedicule chimney-piece and traces of several others.

Whether Smith experimented with designs such as these at Ankerwycke is not known. Fashions and ideas were evolving rapidly during the third quarter of the sixteenth century. A lot can change over the 16 years between the building dates of Ankerwycke and Hill Hall. Nevertheless, it would be amazing to consider Ankerwycke as a transitional house demonstrating Smith's ideas, intellect and great interest in maths and the renaissance.

Smith made Hill Hall his main residence. relocating there in the 1570s to oversee building works. He left a bailiff, Thomas Hurste overseeing the house and farm at Ankerwycke.

Smith later died at Hill Hall on the 12th of August 1577, and was buried at the adjacent church. His property was inherited by his younger brother, George Smith.

Philippa died childless the following year. His tomb is indeed befitting of a great man.

This great house still survives today, and English Heritage organise guided tours there.

Ankerwycke under the Smith's

George Smith (1520 - 1584) of Ankerwycke 1577-1584

The estates of Sir Thomas Smith in Essex, Surrey and Buckinghamshire were entailed under a settlement made 4th February 1576 by Smith prior to his death. It was "so that they might continewe and be in the name, blud stock and kindred of the said Sir Thomas Smithe" .

Thus Ankerwycke passed to his natural younger brother George Smyth, then in his 60s. He and his wife Isabella, resided at Ankerwycke from 1577, as Lords of the Manor of Ankerwycke and Wraysbury. They had 3 children, William, John and Edward. Their time there was cut short, however, as they both died within weeks of each other - on 9th and 31st March 1584 respectively . It is not known why they died so close together: Was age was a factor? Maybe illness struck them both? Or perhaps an incident occurred which resulted in their untimely deaths?

Upon the death of George Smith in 1584, ownership was conveyed to William Smith. He resided at the Hill Hall mansion in Essex, which had been previously conveyed to him three years earlier [TNA C146/8079,8439]. William Smith, like his uncle, was engaged in matters of politics and crown, attending business in Ireland as well as Spain during his career. In 1590 William Smith married Bridget Fleetwood, daughter of Thomas Fleetwood of the Vache, Buckinghamshire, and had two sons, William (b1599) and Thomas (b 1602), plus four daughters.

Records show that from the beginning of the 1600s the three Buckinghamshire estates of Ankerwycke, Wraysbury and Remenham, as well as Ankerwycke Purnish in Surrey were leased out. The combined area of these estates was 650 acres, which brought a sizeable income.

Previous Page : Tudor History Next Page: Stuart History

© Copyright. All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.